How to Cite

YILDIZ, G., & SAHIN GUCHAN, N. (2018). An Industrial Heritage Case Study in Ayvalık: Ertem Olive Oil Factory. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs, 2(3), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.4715

Journal Of Contemporary Urban Affairs

2018, Volume 2, Number 3, pages 20– 30

An Industrial Heritage Case Study in Ayvalık: Ertem Olive Oil Factory

* PhD candidate. GOZDE YILDIZ 1, Dr. NERIMAN SAHIN GUCHAN 2

1 & 2 Faculty of Architecture, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

Email: gozdeyildiz22@gmail.com E mail: neriman@metu.edu.tr

*Corresponding Author:

Faculty of Architecture, Middle East Technical University, Ankara

E-mail address: gozdeyildiz22@gmail.com

A R T I C L E I N F O:

Article history:

Received 15 July 2018

Accepted 23 September 2018

Available online 13 October 2018

A B S T R A C T

Ayvalık is a pioneer settlement in the West Anatolia with an olive-based industry since its establishment. However, due to fast technological developments and changes in production systems, there is a large stock of derelict industrial buildings within the city center. In addition, few of them are restored under poor conditions as a result of financial profits. This situation puts Ayvalık’s olive industrial heritage which constitutes the identity of the town at critical risk of extinction. Ertem Olive Oil Factory is one of the industrial heritage buildings in Ayvalık dating back to 1910 which is a typical well preserved-medium scale 19th-century olive oil factory including both olive oil and soap productions. The aim of this paper is to discuss a conservation approach for the industrial settlement of Ayvalık by assessing the factory and its close environment through values, problems and potentials. The paper thus begins with brief history of Ayvalık and the effects of industrialization on the city. It continues with theoretical principles of adaptive re-use through contemporary literature and general evaluation of adaptive re-use examples in Ayvalık according to these principles. The third part focuses on the general characteristics of Ertem Olive Oil Factory and its close environment. The final part discusses the conservation approach for the adaptive re-use through values, problems and potentials of the building and Ayvalık.

Keywords: Olive industry; Conservation; Adaptive re-use; Olive Oil Factory; Ayvalık.

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY URBAN AFFAIRS (2018), 2(3), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.4715

www.ijcua.com

Copyright © 2018 Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Industrial heritage places, landscapes, buildings and/or complexes are characterized by a pragmatic value-driven approach due to their construction purposes. They have often been both the reflection of transformation and modernization as a result of the industrial revolution. Industrial buildings usually lost their functions due to the fast technological developments and changes in production systems (Cengizkan, 2006: 9).

"Industrial landscape of Ayvalık" defined by a specific geography, in the Western edge of the Anatolia is accepted on the tentative list of UNESCO in April, 2017 as an outstanding example of social and economic structure of 19th-century industry based on olive-oil production in Western Anatolia (UNESCO, 2017).

This paper focusing on a case study selected from Ayvalık aims to discuss a conservation approach by assessing it and its close environment through values, problems and potentials. In this regard, the first part of this paper comprises a summary of the history and characteristics of Ayvalık as an industrial heritage. The second part contains the comprehensive review of the adaptive re-use principles and interpretation of Ayvalık industrial landscape through adaptive re-use examples. The third part describes the case study -Ertem Olive Oil Factory- and its assessment as an industrial heritage. And the last part provides a conservation approach for the adaptive re-use of the selected case study.

1.1. Understanding the History & Characteristics of Ayvalık as an Industrial Heritage

Ayvalık is a seaside town on the northern Aegean cost of Anatolia which is a province of Balıkesir. The geographical settings of Ayvalık, that is confined by the sea in the west, is surrounded by Ida Mountains and Gömeç plain; Altınova province in the south and Madra Mountain that stretches from the north-east to the south-east in an arch form in the east (See Figure 1). It is situated on a volcanic peninsula. From the west, Lesbos Island can also be seen; on the north-east, there is Gömeç; on the south, there are Dikili and Bergama.

This unique geography is covered with olive groves that are a component of the natural character of Ayvalık constituting almost 41.3 per cent of the region which is the main source of the industrial landscape of Ayvalık. There are more than two millions olive trees which originate from the wild olive (olea olester) that existed as local species among other species and were domesticated and converted genetically endemic species (UNESCO, 2017, para. 4).

Figure 1: Location of Ayvalık (Google Earth, last accessed on September 12, 2016) and its close environment (source: http://www.thefullwiki.org/Ayvalik#Notes, last accessed on August 24, 2016)

According to the written sources, there have been settlements in Ayvalık region since the antiquity. However, there are no clearly-defined information about Ayvalık related with the foundation of the settlement because of the uncertain sources. It was known as Kydonia, capital of Eolia in ancient Greek[1] (Yorulmaz, 2000: 34-38; Psarros, 2004; Şahin Güçhan, 2008). Ayvalık has developed in the region where Christians and Muslims lived together since 1580 and the rapid growth of the settlement started after the 18th century with the increase of olive and olive oil productions (Psarros, 2004; UNESCO, 2017).

The late 18th and the beginning of 19th-century was the period of Ayvalık's development of international trade with the help of İzmir as a metropolis. Ayvalık became one of the important port cities which consists of Rum[2] population. The main activities related with the trade was olive oil and its products such as soap and olive pomace -pirina- in addition to flour. By the help of these developments, the population flourished rapidly. Moreover, in 1803 an important academy that makes Ayvalık an educational center in the Greek world was founded.

In the 19th-century, the north of İzmir region including Ayvalık was defined as 'olive region'. In that period, due to the weakness of the Empire, Anatolia became an open market for the colonialist powers and Ayvalık was one of the important gates for penetrating to the economy. Thus, it drew the attention of foreign investors such as English R. Hadkinson who was a pioneering entrepreneur of olive-oil trade during the industrialization period by introducing the machines instead of the primitive tools in Ayvalık and İzmir. It is estimated that in 1884, he constituted an olive oil factory in Ayvalık. And it was developed in time at the sea shore within the city center (Bayraktar, 1998: 16-17, 23).

In the 101st issue of Servet-i Fünun, for identifying the socio-economic situation of Ayvalık in 1894, it is written that there were 11 districts (mahalle), 1 mosque, 12 churches, 6 monasteries, 26 soap plants, 78 olive oil plants, 40 tanneries, 25 wind-mills, 2 hotels, 2 restaurants, 7 olive-oil and flour factories, 45 furnaces. Moreover, in 104th issue of it, it is mentioned that there were 9 quarries in Sarımsaklı (which gives the name to the stone that used in the buildings in the region 'sarımsak stone'), 14 tile and brick kiln and 7 pitcher kiln. This period contained the industrialization and machine power. When it comes to 1900-1914, according to French commerce annual known as "Annuaire du Commerce 'Didot-Bottin' Etranger 1914, Paris, tome II", the trade activities in Ayvalık increased rapidly. New factories were added to the old ones by the supports of foreign investors through the industrialization effects of Europe. Moreover, these trade activities also led to the establishment of consulates in the town such as Greek, England, Italy, France and Norway (Yorulmaz, 2000: 59-61).

In the second half of the 19th-century, the political and demographic situation of Ayvalık changed. By the accordance with the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, the Rums in Ayvalık were forced to move to different parts of Greece, while the Turks living in Lesbos, Macedonia and Crete were moved to Ayvalık and Cunda. As for the main economic activity of the city that is olive industry was continued by the Turks, especially after 1960s -almost 37 years- (Şahin Güçhan, 2008: 84). After this turning point, it was remarked that the main economic activities were still same as olive, olive oil and soap production. In 1923, there were 32 olive-oil mills and 28 soap factories in Ayvalık (Yorulmaz, 2000: 60).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Adaptive Re-use as a Strategy towards Conservation of Industrial Heritage in Ayvalık

The most profound impact of industrialization on industrial areas in urban settlements was preventing the industrial activities in the city center by closing the traditional factories because of changing technologies and new demands. And they moved the industrial activities to outside the city center. Thus, industrial heritage within the centers became derelict (Föhl, 1995; Köksal, 2005).

The same also happened for Ayvalık's industrial heritage. Through the 1972 Development Plan, prepared by Architect Yavuz Taşçı, it was planned that industrial activities which had been hold in the traditional factories within the city center causing the pollution due to their functions, were moved out of the city center. This decision started to be implemented by the 1980s and the industrial activities started to be continued outside the city, near Çanakkale-İzmir Highway, inside the new buildings.

This inevitable transformation that comes due to the technological developments (modernization of the method), solved some problems in the city. However, it caused the majority of the industrial buildings within the city center to become abandoned/non-functional. And today, while half of the industrial buildings are abandoned, the other half of them are converted into different functions some of which are done by ignoring the values. This situation leads to a loss in Ayvalık's industrial characteristics which creates a danger of extinction on the identity of the site. To overcome this problem, it is necessary to define principles of adaptive re-use of such buildings.

Nowadays, repairing and restoring existing buildings for sustainable use has become a creative and effective challenge which is often called 'adaptive re-use'. According to Brooker and Stone (2004: 26) 'adaptive re-use' (in other words, re-modeling, retrofitting, conversion, adaptation, re-working, rehabilitation or refurbishment) means that "the function is the most obvious change, but other alterations may be made to the building itself such as the circulation route, the orientation, the relationships between spaces; additions may be built and other areas may be demolished".

Re-using our heritage building stock is one of the most effective strategies to conserve them. And industrial buildings are the most appropriate heritage buildings to re-use them since they offer great opportunities for transformation of the sites. Binney et al (1990) tried to identify four advantages of industrial buildings for adaptive re-use: 1) Their walls are solid and the floors are made to carry massive weight. If they are being well maintained, they have a life of centuries which make them suitable for adaptive re-use. 2) Most of them are laid out open plan and can be refurbished and adapted for variety of uses. 3) Benefits of re-used industrial buildings such as new job opportunities which often give a certain sense of prestige and promote the development of local economy. 4) The setting of industrial buildings such as being close to the water sources and open land surroundings has quite unexpected potentials. Therefore, adaptive re-use of industrial buildings offers great opportunities for large scale regeneration.

A number of publications have been written on what is considered 'good practice' for adaptive re-use. Among the contemporary literature, 1970s up to the present, three different approaches related with the new design principles were identified on adaptive re-use by considering only the field of heritage conservation and architecture by scholars. These are shortly given below:

A) Programmatic approach (contemporary use)

Dwellings, schools, universities, art centers, museums as well as mixed-used are among the functions located in the former industrial buildings/sites. Trinder and Föhl (1992) stated that there are different areas of new usage for the obsolete industrial structures from classical museum to interactive museum. There are also re-use examples such as concert halls that give the possibility to experience this activity in different ambient. The gas depots converted into diving schools or chimneys reused as the climbing wall are the other examples in that sector.

However, as manufacturing technology, in the case of industrial buildings is a crucial factor that influenced the development of architectural characteristics, except for stylistic, the design principle that unites all the elements into a whole is the 'technological functionalism'[3]. Therefore, for the industrial buildings/sites, technological functionalism can be understood as a principle of aesthetic integrity of industrial heritage which also affects the functional integrity in re-use. Understanding the technology of the manufacturing process, from the aspect of industrial archaeology, machines and buildings that represent their physical frame is equally important.

In a post-industrial society, when these buildings can no longer continue their original uses, the problem of conserving the archaeological value of industrial heritage which is defined as technological functionalism, comes to the fore. The characteristics of the industrial buildings/sites reflect their technological manufacturing process which unfolded in them, or still does. And technological functionalism is limiting factor in adaptive re-use in terms of contemporary use as well as related interventions. Proposing any other function for the former industrial buildings, except of converting into a museum of industry, is contradictory to its archaeological value according to industrial archaeologists (Rogic, 2009: 42).

On the other hand, Föhl (1995) mentioned that the museum as a new function is the first thing coming to mind and preferred method for preserving its archaeological value. However, it should be pointed out that museum as a new function became very common method through increasing number of them in the sector. As a result of that, the necessity of them should be thought for each case.

Nevertheless, it is important that new function should be given to the historic buildings continually and increasingly being adapted for a whole range of functions instead of freezing the history. In each of these functions, the characteristics of the existing building and linking it with the design principles are essential.

B) Design Principles of Interventions

In the contemporary literature, design principles are mainly divided into three categories which the alterations to existing fabric are low, medium and high. Brooker and Stone (2004) (intervention-insertion-installation), Feireiss and Klanten (2009) (Add-on, inside-out, change clothes), Jager (2010) (addition-transformation-conversion) and Rogic (2009) (coexistence-imposition-fusion) are the ones among the authors who were dealing with this approach of adaptive re-use. They discussed the design criteria and formulated them according to the good example projects.

Basically, all abovementioned models show us that the main criterion for the definition of design principles is the relationship between the existing building and the new intervention. For each model, one design principle was presented which implies dependence on the existing building and minimal change. The original building conducts the intervention and decisions. And all characteristics of the new elements derive from characteristics of the existing one.

For instance, according to Brooker and Stone (2004), the design principle of "Intervention", even though it allows for a substantial change, implies the predominance of the old building as all the characteristics of the new elements depend on the character of the existing building. Second design principle, "Insertion", preserves the image of the old building but changes substantially its inner spaces, making both old and new equality present and dominant. The third design concept, "Installation", implies the highest autonomy of the new elements, both materially and structurally,

Consequently, there are several approaches related to design principles for 'good practice' which developed by the scholars as mentioned above. The criteria for the design principles were mainly material relationship-structural dependence and formal-spatial organizations in terms of relationship between the old and the new.

C) Technical Aspects of Re-use

This approach indicates fire resistance, thermal performance, and acoustic performance, prevention of damp penetration, condensation and timber decay. Energy efficiency is another key point for this approach. It is also important to focus on how to adapt a building so as to ensure it in the best way for the new function's technical requirements. Optimizing the new use requires a detailed assessment of many aspects related to its values, existing condition such as structural layout, building capacity for the new use, its potential to meet standards (Bullen&Love, 2009).

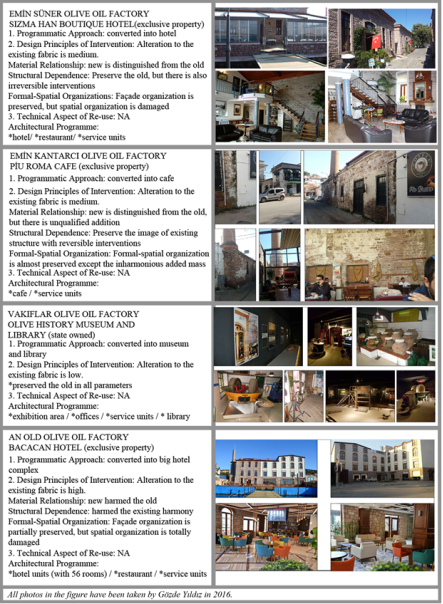

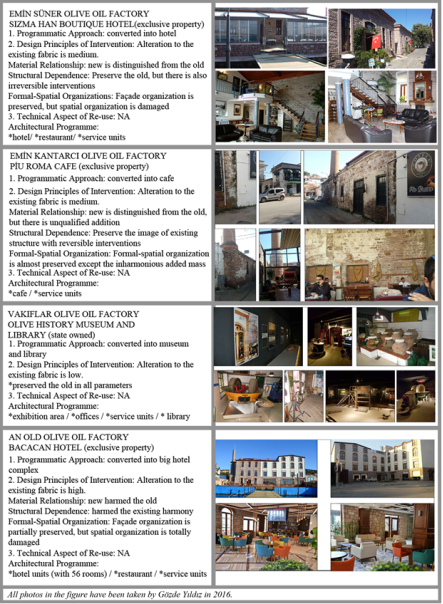

In addition to the above given adaptive re-use approaches, it is necessary to make a critical evaluation of selected adaptive re-use examples in Ayvalık in order to understand the site (See

Figure 2).

Currently, there are factories with a large program which are more than twenty in number within the building stock in Ayvalık. Some of them are being used for new purposes of which are mostly cultural, touristic and administrative purposes. For instance, state-owned ones, Vakıflar Olive-Oil Factory and Kırlangıç Factory are being used for public interest. While Vakıflar Olive-Oil Factory was converted into Olive History Museum that represents the industrial past of Ayvalık, Kırlangıç Factory Complex was converted into the administrative purpose for Ayvalık Municipality and social center for local people. On the other hand, those owned by a private entity are generally converted into touristic purposes such as hotel, cafè which is shaped according to the stakeholders.

Within the scope of the study, selected adaptive re-use examples in Ayvalık (See

Figure 2) were discussed according to the theoretical principles of good practice, their contribution to the site and their negative effects as well. Here, the intention was how theoretical principles are applied to the practice, specific to Ayvalık. These chosen examples originally constructed as olive-oil and/or soap factories, located in the northern part of the port, close to Ertem Olive Oil Factory. This investigation is important for comprehending the site demands, what should or should not do for Ayvalık when constituting the conservation approach and principles for Ertem Olive-Oil Factory and Ayvalık as well.

For Ayvalık, the continuation of the olive industry as a tradition at the different zone of the town and re-functioning traditional industrial buildings for food culture tourism (gastronomic tourism) or re-functioning as hotels have caused the transformation of the city from an industrial center to a touristic-commercial center.

It is obvious that re-functioning of these industrial buildings for touristic purposes is a way to preserve them for the future of Ayvalık as suggested by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 1984 through a research that was made by Tourism Bank. However, while giving a new function regarded with touristic purposes, the capacity of the existing building becomes essential in order to prevent the negative effects of tourism. As seen on Bacacan Hotel example, the new function is not compatible with the original capacity of the building. And it damaged the old.

Figure 2: Selected Ayvalık Adaptive Re-use Examples for the evaluation of the site within the scope of the study.

From the programmatic point of view, it can be said that most of the examples make a contribution to the site in order to provide the sustainability. Moreover, the intention of giving the museum example (Formerly, Vakıflar Olive-Oil Factory) is to understand the site demands towards developing a conservation approach for Ertem Olive Oil Factory. Because, while giving a function as museum, the necessity of it for the site should be analyzed. Thus, in Ayvalık, there is a museum of olive history that one can see the production processes, primitive and 19th-century processing tools, information about family enterprises. In addition to Olive History Museum, there is also Rahmi Koç Museum in Cunda (Formerly, Taxiarchis Church).

For their conservation approaches, it can be concluded that the successful ones have the acceptable relation between the new and old. Generally, minimum interventions provide the success as is seen in the examples of Museum-Library, Piu-Roma Cafè due to their compatible functions. On the other hand, hotel examples have some additions due to their new program's requirements. In that sense, both examples, Sızma Han Boutique Hotel and Bacacan Hotel, have irreversible interventions which damage the existing structures.

Consequently, the new functional requirements can be provided through comprehensive design principles by establishing a good relationship between new and old. And it must be succeeded by analyzing the buildings both technological context and its reflection to the architecture. Generally, when the technological functionalism is used as a guide for constituting the design principles, a good relationship between new and old is achieved for adaptive re-use of industrial buildings.

3. Understanding and Assessment of Ertem Olive Oil Factory as an Industrial Heritage

Ertem Olive Oil Factory (See Figure 3) is one of the industrial heritage buildings in Ayvalık dating back to 1910 constructed before the population exchange -1923- by a Rum named Anastasyos Yorgolos (Efe et al., 2013: 65). The factory was used by several owners for producing olive oil and by-products. In 1952, the ownership of the factory took over to Ertem Brothers who give the name to the factory itself. Ertems who immigrated from Crete in 1924, was settled in Ayvalık after the population exchange. They were one of the important families that come from olive trade originated family and they operated the factory until 2000 (Efe et al., 2013: 65). Today, the ownership of the factory belongs to a Turkish Doctor who lives in the USA. It is abandoned and under the risk of destruction due to the factors of human and nature since 2000.

Figure 3: Ertem Olive Oil Factory, top: view from the sea; bottom left: the most elaborated façade; bottom right: entrance façade (taken by Gözde Yıldız, 2015)

Figure 4: Top Left: cadastral plan (obtained from municipality); Top Right: site plan (prepared by the author, 2016), Bottom: physical layout of the building (Google Earth image, 2016 is digitally manipulated by the author)

The building lot (See Figure 4) which is located on 14. Street, Sakarya District in Ayvalık/Balıkesir-Turkey, covers an area of 1125 m², of 582 m² which is occupied by the factory. The factory is located at the north-east part of the lot. It is composed of three blocks (See Figure 5) adjacent to each other. The main entrance to the factory is provided from 14. Street, from the middle block named as '2nd Block'. The courtyard entrance is also provided from 14. Street, through a courtyard door that is adjacent to the factory.

Figure 5: Blocks forming the factory, source: Gözde Yıldız, 2016.

People leave their cities to have a healthier life, '1st Block' of the factory named as 'soap production block' (Sabunhane Block), has rectangular plan type located on the northern edge of the lot. It is two-storied block that is measured 8x23.5 m in plan dimensions and 7.5 m high from the ground level. It is constructed with the stone masonry system at the ground floor and brick masonry system at the first floor. The ground floor of this block was arranged with five different spaces for the preparation of the soap production and partially olive oil production. The first floor of this block was arranged as a single large space for the soap production processing unit. The chimney is located at this block which is made out of brick. The entrance is provided from three sides of the block. '2nd Block' of the factory named as 'olive-oil production block' (Yağhane Block), has rectangular plan type located in the middle of the other blocks. It is also two-storied block that is measure 8x15.9 m in plan dimensions and 7.45 m high from the ground level. It was arranged as a single large space on both floors. While ground floor of this block serves as olive oil processing unit, the first floor of it serves for the preparation. It is constructed with the brick masonry system and cut stones are used at the corners. The main entrance to the factory is provided from this block. There is another entrance from the west part of it which is located on the courtyard. Reaching to the first floor is supplied from this block by the iron stairs that are located inside.

'3rd Block' of the factory named as 'Annex Block', has rectangular plan type which is two-storied block. It is 5.5x14.9 m in plan dimensions and 6.15 high from the ground level. '3rd Block' is the part of the factory that added lately as a storage for productions and resting places for the workers. It is a reinforced concrete structure that was articulated to the '2nd Block'. The entrance is provided to this block from the ground floor of it. Access to the first floor of this block is provided through a concrete stairs located in the courtyard adjacent to '2nd Block'. (See figure 6).

Figure 6: Ertem Olive Oil Factory (taken by Gözde Yıldız, 2016)

Accordingly, the factory which housed both olive-oil and soap productions, is two-storied building that was constructed with stone and brick masonry technique in Neo-classical style as similar ones in Ayvalık. Architectural and technical (process) elements of it which form the architectural characteristics of the structure have still survived as they are or with their traces. Almost all changes throughout the history are because of the developments in production processes and related spatial requirements. Thus the factory still has its originality (See Figure 6). Moreover, one of the important technological elements, the steam engine of the factory, is exhibited in Rahmi Koç Museum in İstanbul today.

3.1. Assessment of the Factory as an Industrial Heritage and Possible Conservation Proposals

Assessment regarding Ertem Olive Oil Factory can be defined into two contexts considering the building integrated entity within the city. Thus, in order to discuss a conservation approach for the factory; problems, values and potentials should be identified for Ertem Olive Oil Factory and for Ayvalık as well.

To begin with the city scale assessments, Ayvalık has an important silhouette from the sea due to having olive-oil and soap factories lying along the coastline with their chimneys. Courtyards of the buildings and narrow streets are important open areas that have unique vista points as a link with the sea and settlement pattern. However today, the courtyards of the buildings which are the important open areas of the site are being used as car parking area, private spaces for the ones that have been restored for different uses or they are not being used because of abandonment. Hence, it is hard to find a place to connect with the sea as a visitor or an inhabitant.

In addition, one of the important problems for Ayvalık is the transaction of the properties. Today, most of the inhabitants prefer to stay in apartments, thus they sell their houses for purchasing the new one located outside the center. On the other hand, the historical buildings in the city center take the attention of intellectuals, mostly from İstanbul, Ankara and accordingly, prices rise. This situation causes the seasonal usage for the buildings. As a result of this, the living population within the center decreased. Although this situation creates decreased living population problem within the city center, it also gives a potential to the site in terms of re-functioning abandoned industrial buildings through their use value for artistic purposes by aforementioned intellectuals from Ankara and İstanbul who chose Ayvalık to stay for seasonal artistic activities, workshops, festivals such as Taste Festival, Music Festival that is specific to Ayvalık.

Another problem of the site is the abandonment of the traditional industrial buildings within the center. While few of them are re-used for cultural, commercial and touristic purposes in the northern part of the port, others are mostly abandoned such as Ertem Olive Oil Factory. Thus, negligence creates physical problems such as material, structural decays. For the restored ones, the problem is irreversible interventions that damage the buildings' originality. Those can be considered as physical problems of the city.

Although the original character of the city is damaged with the new interventions and aforementioned problems, the industrial identity of the town is still visible. All characteristics of the city such as existing traditional fabric with natural values of the site, are created potentials for the city. These features of the area also give touristic attractions to the site and to the factory. Existing commercial and cultural activities, touristic services in the city and surroundings of the factory, give economic value and potential to the area and to the factory itself. It can be said that Ayvalık is an important touristic and cultural area with its boutique hotels, museums, festivals and related events. This situation creates a big potential for the site in terms of improving this socio-cultural features.

Furthermore, the strong relation between Lesbos and Ayvalık is also important. It comes from the history, as mentioned by Psarros (2004), Ayvalık was the agricultural hinterland of Lesbos and known as 'Coast of Mytileneans'. In the history, there was always continuous trade between these settlements. And the population exchange in 1923, creates another cultural, political-social common point for these settlements. And today, these strong relations between Ayvalık and Lesbos is still continuing. The transportation network between Lesbos and Ayvalık as a result of this relationship affects the touristic attraction of each city as a potential. Accordingly, being located at the very center of the city, near the coast line, gives an important role to the factory. Its specific location that directed to the sea, within the city center is a value and potential. The well-preserved architectural features of the factory such as original plan schema, spatial organizations, are important potentials in order to adapt the building into the new life. Moreover, its big courtyard confined by the sea is another potential for new uses. Accordingly, spatial characteristics, due to serving for special purpose, related production process, which consists of valuable elements or their traces have big potential for exhibition purposes. They constitute specific ambient for new attributed functions. Therefore, the factory has functional and technological value by having specific elements inside of it. In addition to those, the valuable gastronomic culture of Ayvalık has a big potential in order to give the second life to the building with the conservation proposal.

Within this context, Ertem Olive Oil Factory which is one of the well-preserved 19th-century olive oil factories owned by a private entity as an industrial heritage in Ayvalık should respond both public demand and owner needs in terms of programmatic approach. Moreover, there are already industrial museums in Ayvalık and close surroundings that one can see these cultural rituals coming from the history. Thus, in order to avoid the increasing number of museums in the site, the factory can be converted into multi-functional uses by referring the cultural events of Ayvalık. It is a very appropriate place for developing of these cultural backgrounds of the city such as taste festivals, music festivals, historical and cultural discussions, etc. The factory can host all of these events through its originality which behaves like an exhibitive object due to its technological value that shapes its architecture. Regarding the originality of the factory which was used for the same purpose -'olive oil and soap factory'- from its construction until its abandonment, all design principles should be highly respected. All actions as a reason for changes should be considered as valuable, even though they may have negative impacts. Thus, all interventions should be kept in minimum and they should be supported with technical specifications without harming the existing structure in order to provide the new function requirements (See Table 1).

Table 1: Conservation Proposal for Ertem Olive Oil Factory

4. Conclusion

Industrial buildings such as Ertem Olive Oil Factory are one of the main symbols of the socio-economic past of the towns as being cultural assets with their technological values which drives their architectural characteristics. They are important icons of our industrial-technological past due to representing the technological developments throughout the time. Since the main aim of this paper is to discuss a conservation approach for Ertem Olive Oil Factory, the first step is to investigate an accurate conservation method or approach for industrial buildings and re-evaluate Ayvalık industrial heritage through selected adaptive re-use examples according to this developed conservation approach by benefited from the contemporary literature. Accordingly, three main parameters come to the fore for strategies of adaptive re-use of industrial buildings. These are the programmatic approach (new appropriate function), design principles of intervention (principles related to physical problems which are categorized as a material relationship, structural dependence and formal-spatial organization) and technical aspect of re-use (technical requirements for new function). Moreover, ownership statue of the buildings is another important factor while re-functioning them. That's why re-adaptation of industrial buildings is always problematic in the world. Accordingly, industrial buildings are generally converted into multi-functional uses and/or museums. It is because of their technical values that are production equipments unfolded inside of them which also give 'aesthetic value' to these buildings. They represent a symbolic and commemorative value for the collective memory as being a witness of the industrial-technological history. Thus, in order to conserve these buildings, minimum intervention is essential for the success. And it can be provided by using the technological functionalism as a guide for the design principles which is also the limiting factor for adaptive re-use.

References

Alcock, I., White, M., Wheeler, B., Fleming, L., & Bayraktar, B. (1998). Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyete Ayvalık Tarihi, Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu [History of Ayvalik from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic, Atatürk Culture, Language and History High Council], Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi, Basım Ciltevi, Ankara. https://books.google.com.tr/books/about/Osmanl%C4%B1_dan_Cumhuriyet_e_Ayval%C4%B1k_tarih.html?id=pqxtAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

Bınney, m., Machın,F., & Powell, K. (1990). Bright Future: The Re-use of Industrial Buildings, SAVE Britain's Heritage, London. https://www.savebritainsheritage.org/publications/publications-in-print

Brooker, G., & Stone, S. (2004). Re-readings: Interior Architecture and the Design Principles of Re-modelling Existing Buildings. RIBA Enterprises, London. https://www.ribabookshops.com/item/rereadings-interior-architecture-and-the-design-principles-of-remodelling-existing-buildings/82304/

Bullen, P., & Love, P. E. (2009). Residential regeneration and adaptive re-use: learning from the experiences of Los Angeles. Structural Survey , 27 (5), 351-60. https://doi.org/10.1108/02630800911002611

Cengizkan, M. (2006). Endüstri Yapılarında Yeniden İşlevlendirme: "İş" i Biten Endüstri Yapıları Ne "İş" e Yarar. (“Re-Functioning in Industrial Structures:“ Industrial Structures That Completed the Work lendirme What is Business) TMMOB Mimarlar Odası, 45(3), 9-11. http://www.mimarlarodasiankara.org/dosya/dosya3.pdf

Efe, R., Soykan, A., Cürebal, İ., & Sönmez, S. (2013). Edremit Yöresi Yağhaneleri [Edremit Region Oils]. Ana Gıda-Komili, İstanbul. http://www.komilizeytinyagi.com.tr/Files/ekitap/edremit-yoresi-yaghaneleri.pdf

Fohl, A. (1995). Bauten der Industrie und Technik, Schriftenreihe des Deutschen Nationalkomitees für Denkmalschutz. (Buildings of Industry and Technology (Series of the German National Committee for Monument Protection) Band 47, Innern. https://www.zvab.com/9783922153030/Bauten-Industrie-Technik-Schriftenreihe-Deutschen-3922153038/plp

ICOMOS. (2003). Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage, Moscow, Retrieved from http://www.icomos.org/18thapril/2006/nizhny-tagil-charter-e.pdf

Jager, F. (Ed.). (2010). Old&New. Design Manual for Revitalizing Existing Buildings, Birkhäuser, Basel. https://issuu.com/birkhauser.ch/docs/oldnew

Kabasakal, S. (1987). A study on re-functioning of the 19th century industrial buildings, a case study in Ayvalık center area. Unpublished MSc. dissertation, Department of Architecture-Restoration, METU, Ankara. http://www.mimarlikdergisi.com/index.cfm?sayfa=mimarlik&DergiSayi=383&RecID=3054

Köksal, T. G. (2005). İstanbul'daki Endüstri Mirası için Koruma ve Yeniden Kullanım Önerileri [Protection and Reuse Recommendations for Industrial Heritage in Istanbul]. unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Architecture, ITU, İstanbul.

https://polen.itu.edu.tr/bitstream/11527/4204/1/4105.pdf

Manisa, K. (2013). Endüstri Mirası Olarak Zeytinyağı İşlikleri.( Standing as Industrial Heritage - Old Olive Oil Works and Architectural Features in Bergama Region (Ege Mimarlık Magazine) Mimarlık Dergisi (369), 77. http://www.mimarlikdergisi.com/index.cfm?sayfa=mimarlik&DergiSayi=383&RecID=3054

Plevoets, B., & VAN C. K. (2011). Adaptive Re-use as a Strategy towards Conservation of Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review. WIT Transactions on the Built Environments , 18, 155-164.

https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-the-built-environment/118/22728

Psarros, D. (2004). 'Kydonies-Ayvalık'ın Kentsel Tarihi ['Urban History of Kydonies-Ayvalik]. In ŞAHİN GÜÇHAN, N. (ed.) Ege'nin İki Yakası I-Ayvalık'ın Kent Tarihi Çalışmaları Bildiriler Kitabı, 28-30 October 2004, inprint, Ayvalık. http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2008/cilt25/sayi_1/53-80.pdf

R., K., & Feıreıss, L. (Eds.). (2009). Build-on: Converted Architecture and Transformed Buildings. Gestalten, Berlin. https://pdfkingdom.com/pdf/downloads/build-on-converted-architecture-and-transformed-buildings.pdf

Rogıc, T. (2009). Converted Industrial Buildings: Where Past and Present Live in Formal Unity. Phd dissertation, TUDelft, Amsterdam. https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid:20de163d-db70-415d.../download

Sogancı, M. N. (2001). Architecture as palimpsest:Re-functioning of industrial buildings within the scope of industrial archaeology, Unpublished MSc. dissertation, Department of Architecture, METU, Ankara.

Sahin G, N. (2008). 'Tracing the Memoir of Dr. Şerafeddin Mağmumi for the Urban Memory of Ayvalık'. METU Journal of Faculty of Architecture, 25(1), 53-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235674144_Tracing_the_Memoir_of_Dr_Serafeddin_Magmumi_for_the_Urban_Memory_of_Ayvalik

UNESCO (2017), Ayvalık Industrial Landscape, http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6243/

Yerliyurt, B., & Manisa, K. (2014). Re-use of Traditional Olive-oil Mills in the Context of Alternative Tourism for Sustainable Social and Ecologic Environment; industrial heritage at Ayvacık Coastal Area. ALAM CIPTA : International Journal of Sustainable Tropical Design Research and Practice (Volume 7, No. 2, December 2014, Pages 37 to 50). http://www.frsb.upm.edu.my/dokumen/FKRSE1_154-540-1-PB.pdf

Yorulmaz, A. (2000). Ayvalık'ı Gezerken. Geylan Kitabevi, Ayvalık. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18277742-ayval-k-gezerken

How to Cite

YILDIZ, G., & SAHIN GUCHAN, N. (2018). An Industrial Heritage Case Study in Ayvalık: Ertem Olive Oil Factory. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs, 2(3), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.4715

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivs 4.0.

"CC-BY-NC-ND"

[3] For further information about ‘Aesthetic Integrity’ and ‘Technological Functionalism’of Industrial Buildings, see (Rogic, 2009, Chapter 1)