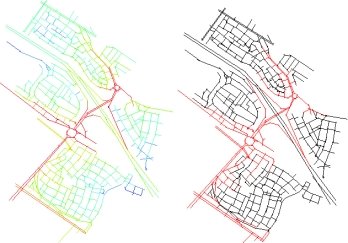

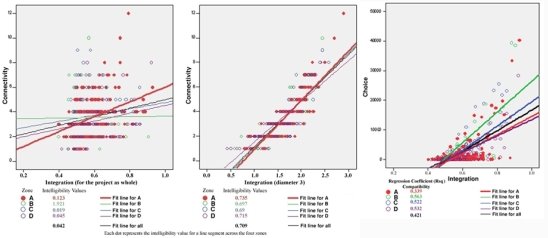

In the light of the foregoing discussion, the high crime rate reduced in zone A can be interpreted, where many factors have led to this situation. First, the high values of both integration and intelligibility. Second, the relatively deep penetration of the core of integration into the region; makes the region more accessible by strangers. Third, and most importantly, the weak coincidence between spaces commonly used by residents and those easily accessed by strangers. The third factor eliminates the residents’ control and surveillance of strangers, which seems essential for the security of residential areas.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

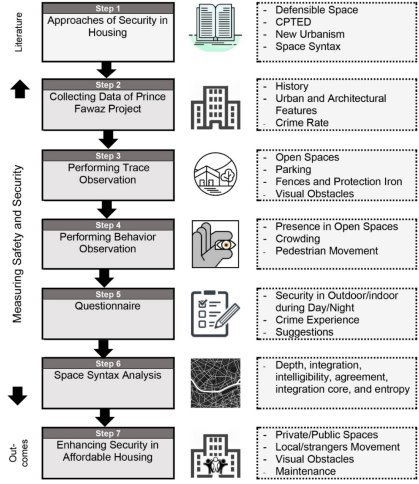

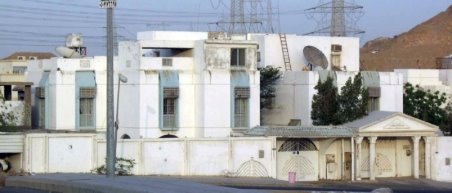

On the theoretical level, the case study shows that none of the approaches concerned with security in residential areas reached up to completion; but each has aspects that partly work. Prince Fawaz project clarifies that the unidentified, uncontrolled and inactive open spaces are unsafe areas that raise the residents’ fear in accord with Defensible Space and CPTED. While Defensible Space claims territoriality and access control, the case study shows that streets in which residents and strangers’ movement matches enjoy a higher level of security. This agrees with CPTED, New Urbanism and Space Syntax. To enhance security in affordable housing, it is suitable to examine it case by case. A detailed record for types, places and time of crimes is a major component. A comparative analysis of projects can help to refine the results too.

Based on trace and behaviour observation, as well as the questionnaire, the periphery open spaces constitute unsafe areas. Space syntax illustrates that they are accessible by outsiders with little compatibility with residents. Such spaces provide uncontrolled access to the project resulting in a threat for the residents. Controlling access to these spaces, a process that some residents began to do on their own, is a recommended approach. As extracted from the questionnaire, organized and clean spaces reflect the sense of security among residents and provide an inappropriate environment for criminals. Allocating and identifying specific activities for spaces encourage users to use them as intended. It is equally important to allocate open spaces to specific entities to organize and maintain them.

Spaces around mosques are safe during prayer time and vice versa as reported by the questionnaire. The movement to/from mosques (five times along the day) bring life to the area during prayer times and makes residents feel safe. While the lack of pedestrians in between prayer times accompanied by the existence of visual obstacles, according to trace observation, demonstrate the feeling of fear. Vegetation and rearranging visual obstacles, like water tanks and garbage containers, are expected to remedy fields of vision offering a comfortable environment for residents. Identifying areas for labour to gather in at night can keep an eye on the spaces, add courtesy and hence maintain security.

Zone A, the highest crime rate according to the questionnaire, is the most crowded according to behaviour observation and the most accessible and penetrated according to Space Syntax. But, the agreement between residents and strangers’ movement is the least. This emphasizes the fact that strangers' presence or movement through the residential area has limited influence on crime when they are accompanied by residents. On contrary, the absence of residents provides an opportunity for crime in spaces mostly accessed by strangers. This is typical with spaces around shops. It is recommended, thus, to reformulate movement routes to drive strangers to routes used by residents (integration core). Otherwise, the integration core could be re-allocated to penetrate the four zones instead of surrounding them; and pass by the commercial zone and mosque in each zone. This is expected to enhance intelligibility across the project encouraging movement on carefully selected spines that are compatible with residents’ movement. Zone A, in specific, requires more compatibility between residents and strangers’ movement to provide an adequate level of surveillance. The rest of the areas, with low intelligibility values, could be turned into controlled private and semi-private entities to block strangers to navigate through.

Comparing zone, A, the highest crime rate according to the questionnaire, with zone B and D, the least in crime rate, raises the issue of size and population of housing development. Results advocate small scale development with a straightforward urban pattern.

Fear of crime can be generally eliminated by providing sustainable maintenance for the project spaces and movement routes; vegetation can play a significant role herein. Protection tactics justify the low fear of crime achieved in the project despite the recorded crime rate. However, protection tactics need to be studied, examined and developed in integration with the design not imposed on it; this is an interesting future scope of research.

Acknowledgement

This article was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. The author, therefore, acknowledges with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Abdullah Eben Saleh, M. (1999). Reviving traditional design in modern Saudi Arabia for social cohesion and crime prevention purposes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 44(1), 43-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(98)00107-8

Abu Shama, A. (2007). Violence crime and methods of facing it in the Arab countries. Riyadh: Naif Arab Academy for Security Sciences. (Arabic).

Adel, H., Salheen, M., & Mahmoud, R. A. (2016). Crime in relation to urban design. Case study: The Greater Cairo Region. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 7(3), 925-938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2015.08.009

Al Beshr, K. (2000). Fighting crime in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Naif Arab Academy for Security Sciences. (Arabic).

Al Hazza', W. (2001). Affordable housing Seminar on Future of Housing in the City of Riyadh, The High Commission for the Development of Riyadh, Riyadh. (Arabic).

Anna Alvazzi del Frate, J. N. (Ed.). (1993). Environmental Crime, Sanctioning Strategies, and Sustainable Development. United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute.

Austin, D. M., Furr, L. A., & Spine, M. (2002). The effects of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of safety. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(5), 417-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(02)00148-4

Ballintyne, S., Pease, K., & McLaren, V. (Eds.). (2000). Secure Foundations: Key Issues in Crime Prevention, Crime Reduction and Community Safety. Institute for Public Policy Research.

Bartol, C. R., & M., B. A. (Eds.). (2006). Current perspectives in forensic psychology and criminal justice. USA: Sage Publications.

Branas, C. C., Cheney, R. A., MacDonald, J. M., Tam, V. W., Jackson, T. D., & Ten Have, T. R. (2011). A Difference-in-Differences Analysis of Health, Safety, and Greening Vacant Urban Space. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(11), 1296-1306. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr273

Brown, B. B., & Altman, I. (1983). Territoriality, defensible space and residential burglary: An environmental analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(3), 203-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80001-2

CNU. (2001). Charter of the new urbanism. New York: Congress for the New Urbanism.

Cozens, P., Hillier, D., & Prescott, G. (2001). Crime and the design of residential property – exploring the perceptions of planning professionals, burglars and other users: Part 2. Property management, 19(4), 222-248. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005784

Cozens, P. M. (2002). Sustainable Urban Development and Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design for the British City. Towards an Effective Urban Environmentalism for the 21st Century. Cities, 19(2), 129-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(02)00008-2

Donovan, G. H., & Prestemon, J. P. (2010). The Effect of Trees on Crime in Portland, Oregon. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 3-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510383238

El-Torky, M. (2015). Reduction of crime rates in Saudi Arabia by 10% in the Past Year. Aleqtisadiah, 8035, 11 October. Riyadh: Saudi Research and Publishing Company. (Arabic).

Elbadawi, I. (1991). The role of planning in promoting safer communities. Canada: Dalhousie University.

Elgarmadiand, A. S., & Özer, Ö. (2018). The relationship of crime to the street network using the space syntax theory, Case study Al-khums City-Libya. International Journal of Latest Research in Humanities and Social Science (IJLRHSS), 1(7), 21-27. http://www.ijlrhss.com/paper/volume-1-issue-7/4.HSS-164.pdf

Elshater, A. (2012). New Urbanism Principles versus Urban Design Dimensions towards Behavior Performance Efficiency in Egyptian Neighbourhood Unit. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 68, 826-843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.270

Foster, S., Hooper, P., Knuiman, M., Bull, F., & Giles-Corti, B. (2016). Are liveable neighbourhoods safer neighbourhoods? Testing the rhetoric on new urbanism and safety from crime in Perth, Western Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 164, 150-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.013

Ghani, Z. A. (2017). A comparative study of urban crime between Malaysia and Nigeria. Journal of Urban Management, 6(1), 19-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2017.03.001

Ha, T., Oh, G.-S., & Park, H.-H. (2015). Comparative analysis of Defensible Space in CPTED housing and non-CPTED housing. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 43(4), 496-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2014.11.005

Hagan, F. E., & Daigle, L. E. (2018). Introduction to Criminology: Theories, Methods, and Criminal Behavior. SAGE Publications.

Harcourt, B. E. (2009). Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing. Harvard University Press.

Hardy, K. M. (1997). Crime prevention through environmental design: A comparative analysis of two Las Vegas apartment complexes (Nevada) School of Architecture, College of Fine Arts

University of Nevada]. Las Vegas. https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=5567144

Hillier, B. (2004). Can streets be made safe? URBAN DESIGN International, 9(1), 31-45. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000079

Hillier, B., & Sahbaz, O. (2005). High Resolution Analysis of Crime Patterns in Urban Street Networks: an initial statistical sketch from an ongoing study of a London borough.

Hillier, B., & Sahbaz, O. (2008). An evidence based approach to crime and urban design, or, can we have vitality, sustainability and security all at once. Bartlett School of Graduates Studies University College London, 1-28.

Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001). Environment and Crime in the Inner City: Does Vegetation Reduce Crime? Environment and Behavior, 33(3), 343-367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916501333002

Lacoe, J., Bostic, R. W., & Acolin, A. (2018). Crime and private investment in urban neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Economics, 108, 154-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.11.001

Lorenc, T., Clayton, S., Neary, D., Whitehead, M., Petticrew, M., Thomson, H., Cummins, S., Sowden, A., & Renton, A. (2012). Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: Mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health & Place, 18(4), 757-765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.001

Maas, J., Spreeuwenberg, P., van Winsum-Westra, M., Verheij, R. A., Vries, S., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Is Green Space in the Living Environment Associated with People's Feelings of Social Safety? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(7), 1763-1777. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4196

Malleson, N., & Birkin, M. (2012). Analysis of crime patterns through the integration of an agent-based model and a population microsimulation. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 36(6), 551-561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2012.04.003

Marques, S. C. R., Ferreira, F. A. F., Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I., & Banaitis, A. (2018). Classifying urban residential areas based on their exposure to crime: A constructivist approach. Sustainable Cities and Society, 39, 418-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.03.005

Marvi, L. T., & Behzadfar, M. (2015). Local Sustainability with Emphasis on CPTED Approach, The Case of Ab-kooh Neighborhood in Mash-had. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 201, 409-417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.194

McCord, E. S., Ratcliffe, J. H., Garcia, R. M., & Taylor, R. B. (2007). Nonresidential Crime Attractors and Generators Elevate Perceived Neighborhood Crime and Incivilities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 44(3), 295-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427807301676

Mohit, M. A., & Hannan, M. H. E. (2012). A Study of Crime Potentials in Taman Melati Terrace Housing in Kuala Lumpur: Issues and Challenges. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 42, 271-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.191

Nasar, J. L., Fisher, B., & Grannis, M. (1993). Proximate physical cues to fear of crime. Landscape and Urban Planning, 26(1-4), 161-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(93)90014-5

Nasar, J. L., & Jones, K. M. (1997). Landscapes of Fear and Stress. Environment and Behavior, 29(3), 291-323. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659702900301

Newman, O. (1972). Defensible space: crime prevention through urban design. New York: Macmillan.

Nubani, L., & Wineman, J. (2005, 2005). The role of space syntax in identifying the relationship between space and crime Proceedings of the 5th Space syntax Symposium on Space Syntax, Delft, Holland. http://spacesyntax.tudelft.nl/media/Long%20papers%20I/lindanubani.pdf

OSAC. (2019). Saudi Arabia 2019 Crime & Safety Report: Jeddah. https://www.osac.gov/Country/SaudiArabia/Content/Detail/Report/29856272-46df-49b5-8c3c-15f4aeafb5da

OSAC. (2020). Saudi Arabia 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh. https://www.osac.gov/Country/SaudiArabia/Content/Detail/Report/f6af335c-d5b7-4087-9086-186575bdfb0f

Pietenpol, A. M., Morgan, M. A., Wright, J. P., Almosaed, N. F., Moghrabi, S. S., & Bashatah, F. S. (2018). The enforcement of crime and virtue: Predictors of police and Mutaween encounters in a Saudi Arabian sample of youth. Journal of Criminal Justice, 59, 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.05.007

Piroozfar, P., Farr, E. R. P., Aboagye-Nimo, E., & Osei-Berchie, J. (2019). Crime prevention in urban spaces through environmental design: A critical UK perspective. Cities, 95, 102411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102411

Robinson, P. E. M. (1997). Places of crime and designing for prevention: a study of York University Campus. Ontario: York University.

SABQ. (2017, 13 October 2017). Decline of crime in Saudi Arabia: security alert, awareness of society and a state that imposed its prestige with justice. (Arabic). . SABQ online newspaper.

Sakip, S. R. M., & Abdullah, A. (2012). Measuring Crime Prevention through Environmental Design in a Gated Residential Area: A Pilot Survey. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 42, 340-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.198

Serpas, R. W. (1998). Common-sense approaches with contradictory results: Does defensible space curb crime? (Publication Number 9900958) [Ph.D., University of New Orleans]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; ProQuest One Academic. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304426725?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true#

Shon, P. C. H., & Barton-Bellessa, S. (2015). The assumption of rational choice theory in Alfred Adler's theory of crime: Unraveling and reconciling the contradiction in Adlerian theory through synthesis and critique. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 95-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.004

Soh, M. B. C. (2012). Crime and Urbanization: Revisited Malaysian Case. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 42, 291-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.193

Sonia Hirt, & Zahm, D. L. (Eds.). (2012). The Urban Wisdom of Jane Jacobs. Routledge.

Taylor, R. B. (2001). Breaking away from broken windows: Baltimore neighborhoods and the nationwide fight against crime, grime, fear, and decline. Oxford, Westview Press.

Thacher, D. (2004). Order maintenance reconsidered: Moving beyond strong causal reasoning. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 94, 381-414.

Wilcox, P. (2015). Routine Activities, Criminal Opportunities, Crime and Crime Prevention. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition (pp. 772-779). Elsevier Inc.

Wolfe, M. K., & Mennis, J. (2012). Does vegetation encourage or suppress urban crime? Evidence from Philadelphia, PA. Landscape and Urban Planning, 108(2), 112-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.08.006

Yazdanfar, S. A. A., & Nazari, N. (2015). Proposed Physical-environmental Factors Influencing Personal and Social Security in Residential Areas. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 201, 224-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.171

Zen, I., & Mohamad, N. A. A. (2014). Adaptation of Defensible Space Theory for the Enhancement of Kindergarten Landscape. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 153, 23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.037