3.1 States’ roles over the respective heritages: post-trauma scenarios.

The role of the states over Heritage has been progressively intense from a managerial perspective. The pre-modern scenarios were based on a private initiative and two basic ideas. The stakeholders of the heritage production and maintenance were so far from the own state since the Heritage concept was even unknown, and the inconsistency of States as protectors and main stakeholders of Cultural Heritage protection was so far of being effective.

A historical overview of Cultural Heritage protections has diverse precedents. The first collection’s concept during the Late Medieval and Early Modern Periods came from the idea of reducing the whole world History into a single closed space to its “antiquarian interest”. The acquisition as a social value, the rarity of different objects, their aesthetic quality as well as the fact of objects being taken from the enemy as a part of wars’ spoils were in the origin of so many collections. This phenomenon is visible in the collections of Pedro Henriquez de Acevedo, the founder of Casa de Pilatos palace in Sevilla, where the pieces are shown to come from the different campaigns of this general caught during his different wars in Italy (16th century). Time, place, and social prestige were factors able to assign certain values and they were criteria for the selection of the materials to be collected.

A second factor played an important in this process, due to the enlargement of the known World after discoveries in America and India. In this case, the social prestige would be substituted for national prestige, as the country can assume a colonialist role. This role was taken by Institutions, most of them religious and the State would symbolize this kind of action through the fact of extrapolation of some elements (usually architectural objects) to other new buildings, as symbols of victory over the enemy. Monuments, as new entities during the 19th century, as well as the new concept of national heritage led societies to consider these new entities as a symbol of power linking in a material way Culture and Power. Colonialism let eradication and pillage of the original Heritage sites, either at local, regional, or international levels. Different reasons were assumed alongside History and these kinds of processes were done in the last regional conflicts.

First World War (1914-1918) was the starting point to use weapons of extreme force with scenarios of heritage destruction, used in this case as a punitive action against the enemy. Second World War (1939-1945) repeated the same schemes enlarging the scale of destruction till the total eradication of settlements. In both cases, it is not possible to talk of collateral effects of war actions but a premeditated strategy with punitive effects to be suffered beyond the end of the war: the disappearance of heritage objects from the collective memory of a country. So many scientific answers to these phenomena were achieved, as a direct positive consequence of that. So many University departments were focused on the destruction processes and their consequences, as well as the development of the restoration theories, linked to the different complex practical cases for recovering the destroyed built heritage.

During the second half of the 20th century, after the II World War, various initiatives converged into a common goal of preserving memories as the way to understand the present and beginning to formalize the future in the planet. UNESCO´s contribution was vital for that. This fact encouraged heritage studies as well as another perspective of the topic: the heritage business. Tourism and Heritage run parallel paths. The use and abuse of these practices are provoking nowadays a double phenomenon: lack of authenticity in such scenarios with an important down in identity terms and exacerbations of heritage assets as objects of sale, either through their temporary enjoyment or through a banalization of the heritage concept.

Cultural Heritage has been, in fact, the conceptual basis of the arousal of nationalist movements. It is normal to see how heritage objects are symbols to reclaim certain old sovereignty status over territories in recent nationalities, as a way to promote social conflicts, either from extremist or chauvinistic perspectives. Trauma interventions and wars do not finish when ceasing fire. Fights continue in a hidden way till achieving social control over territories. There are different manifestations of fight: they go from the simple destruction of monuments of previous cultures on the site as a form of eradication of the history and culture up to distorted interpretations of the same cultural heritage, as a simple manipulation of the facts to translate History into a more convenient version favouring certain religious or political movements linked to the current territorial status.

Post-trauma scenarios led to various options and the Role of International Institutions in conflict territories is considered so important for the recomposition of scenarios where spatial sharing can be possible. A substantial difference between modern and recent contemporary states is related to the attitude facing the Heritage problem. The modern government would play the role of promoting Heritage as a preserver of their memories and in the case of the colonized countries, the role of curator of different local Heritage provoked the abuse of dislocating local memories to the own National Museums. Contemporary governments of countries coming from post-trauma interventions try to control and translate Heritage in a distorted way. Almost all of them try to take advantage of the different scenarios as the best way to command the new heritage landscapes

Two references to post-trauma scenarios are indeed tackling the main issue: Andrieux (2016) summarized the statement in the last 40 years “… heritage has become unwillingly one of the great symbolic stakes of the ongoing conflicts over the planet.” According to Hutchings and Dent (2017) “Heritage will be questioned as a symbolic social construction, a catalyst for appropriation and/or identity-making and the object of memory discourses.” Cultural Heritage becomes in this case a sort of instrument for imposing and challenging domination.

In these scenarios, the contribution of the International Institutions is essential for adequate territorial recomposition, where the Heritagization plays an important role. This process, when applied to the different realities that were inherited (objects, cultures, even intangible memories), is totally necessary for the construction of historical narratives and propose valid Heritage policies promoted by the new governments.

3.2 The Cypriot case

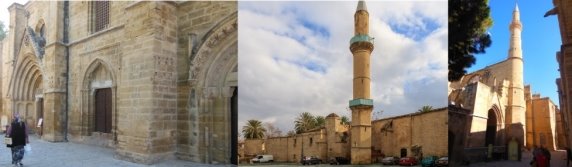

Cyprus presents a unique case in the Mediterranean Basin, as an immense cultural crossroad is. Historically considered as a conflict territory, Cyprus became a laboratory where all the confrontations between Christian and Muslim communities assumed different scenarios: Venice vs. Ottoman Empire, just after Lepanto battle; Ottoman Empire vs. British Empire; and the recent episodes of the civil conflicts between Turkish and Greek communities in the last century (1963–1974).

These facts eased the arousal of cultural crossroads able to configure the third kind of identities, which share the same reduced space of the island, despite the historical controversies.

In the period 1878-1974 Cyprus suffered a sequence of events that branded its history definitively up today. Since the Ottoman cession to the British Administration of the island in 1878 and its later declaration as a British Crown colony between 1925 and 1959, the final independence arrived in 1969 after the liberation struggle in 1955-1959 against the colonial rule. Coexistence between Turkish and Greek communities was short: in 1964, UN peacekeeping forces arrived in Cyprus, with the main purpose of preventing intercommunal clashes between the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. These forces, known as The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) were settled following the resolution 186/1964 of the United Nations Security Council and nowadays they continue on the island with periodical renewals.

In July 1974, Turkish forces invaded and occupied the northern third of the island, according to the Greek version. The Turkish version refers to the idea of Turkish troops’ arrival to the island with the only one objective of protecting the Muslim minority, displaced up to the northern part of the island. Turkish troops are currently settled on the island. UNFICYP troops continue keeping and controlling the buffer zone, that separates both communities during the last 54 years. Both parts were uncommunicated till April 2008, when the Ledra street checkpoint opened. The hard blockage of the intercommunal frontiers ended after 34 years.

This scenario contrasts with the necessary cooperation between both communities for the resolution of territorial common problems: Nicosia Master Plan became vital for that. This urbanistic tool was conceived as a bi-communal initiative to change the image of the city following two urgent actions to resolve the territorial problems caused by an interrupted city. In 1978 an agreement for the preparation of a common sewerage system was achieved. One year later it was agreed to the preparation of a physic master plan, respecting initially the urbanistic decisions of both halves of the city. In 1981 a bi-communal multidisciplinary team was formed to prepare a common planning strategy for Nicosia. The agreement contained two different scales. One first step defined between 1981 and 1984 was the general planning strategy for Greater Nicosia. During 1984 and 1985 an operational master plan for the walled city was developed, being Heritage topics the focus of the project. The positive perspective was using Heritage as a conciliator element between both communities, and the negative aspects referred to the different problems and difficulties to have a reasonable treatment of the archaeological sites.

The assumption of bicommunal projects was the beginning of a sequence of successful collaborations. The restoration of certain Heritage objects became landmarks of a community on the opposite territories. We pay special attention to the works developed by the Bicommunal Technical committee on cultural heritage during the last decade. This group of experts in heritage from both sides has been the key element to develop actions under the UN auspices to promote the cross heritage of the diverse social groups, usually located on the opposite side of the island, divided into two parts after the civil war in 1974, and separated by a buffer zone controlled by UN troops.

The experiences of restoring the heritage objects after the civil war in Cyprus in 1974 were commanded by United Nations through UNDP. The creation of a Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage was possible in 2008 when UNDP contributed to reaching an agreement between both communities of the island about tasks to develop in the Cultural heritage. This bi-communal Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage started to work in 2009 when a Study of Cultural Heritage in Cyprus was requested by the European Commission. This Committee played an important role in the recovering of 70 sites and monuments on both sides of the buffer zone. This important fact is not hiding the definition and development of a more active role of cultural heritage in the ongoing peace and confidence-building process on the island. Since 2012, this committee had the European Commission as a key partner together with UNDP. The program has been spread all over the island with more concentrated actions on the Karpasia/Karpaz area. The map below reflects the whole number of actions developed till now in different scales (see figure 2):

Figure 3. Agios Philon after the restoration, 2021.

Last works in the Karpaz area (Agios Philon and Afendrika complex) were the precedent to the awarded action by Europa Nostra in 2021. (Figure 3)

The reaction of both communities facing the issue of restoration of built elements of the opposite ethnic group has been positive in general terms. The exception was the arson attack on the mosque in Denia, one of the villages located inside the buffer zone. This attack provoked the destruction of the entire roof as well as damages to the structural parts in stone, which obliged a new restoration.

The negative aspects related to the heritage status of the many buildings not yet restored in both parts led leads to dramatic situations in some cases. Abandoned mosques in the South and buildings are victims of vandalism carried by uncontrolled groups. At the same time, a similar statement is happening in the northern part of the island at Monastery of Antiphonitis, close to Esentepe on the northern slope of Pentadaktilos range of the island, close to Girne. Different actions managed by the Department of Antiquities and Museums provoked clashes between both national Administrations. The focus was around the excavations developed in 1983 in Galinoporni /Kaleburnu. Other polemic actions developed by the Eastern Mediterranean University were strongly contested by the southern Administration in places like Akanthou/Tatlısu; Salamis and at Galinoporni/Kaleburnu. The Cypriot Heritage experience, as a sequence of the previous bi-communal projects like the Master Plan for Nicosia, proves the feasibility of finding out common and successful solutions for common problems, basically located on the shared spaces due to the political circumstances. They even prove the possibility of shared responsibility on the projects under the umbrella of International Institutions, in this case through the coordination of UNDP offices.

3.3 The Balkans case

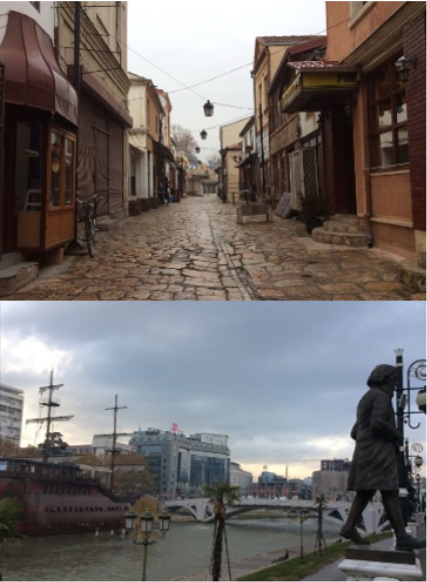

There is a direct relationship between the current political map of the Balkans region and the continuous overlapping of diverse historical layers with their respective repositories of heritage objects, tangible and intangible ones. Roman traces, as well as Byzantian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian presences in the region, according to a conventional traditional vision of the region, seem to explain and justify the complex vision of the region. The heritage strategies of the new states, coming from the division post-civil wars in the period 1991-1999, are dominated by two goals. The first one is the intention of looking for roots without any link with recent history, to reinforce the authenticity of this local identity. The second way is just the opposite, joining several characters, events and monuments of diverse cultures that collaborated on the construction of a territory, as a way to create a new identity, cause of current national pride.

In the first case, we can highlight the efforts of the Kosovar government as a way of reclaiming an own identity before the roman period and far from the colonial status. This is the case of the Neolithic site of ‘Tjerrtorja in Kalabria site, identified almost sixty years ago. It is clear the intention of Memli Krasniqi, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports of Kosovo in 2012 when confirms the fact of the archaeological testimonies reflecting the traces, remains, ruins and artefacts of the past civilization, of the autochthonous population (Berisha, 2012, pp. 3–4) (Figure 4).

In the second case, a simple walk along with the new urban landscape of Skopje, as a way of identifying a new monumentality of the city, reveals the efforts of commemorating the several characters in the region: Mother Theresa can share spaces with old medieval Christian kings of the past. (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Hyjnesha Ne Fron, goddess, by Arben Ilaphastica (left) and the aerial view from Ulpiana archaeological site. Sources: https://twitter.com/illyriens and Carto database (right).

Figure 5. Different scales of the traditional and contemporary Skopje.

Balkans were always a scenario of fights between Christian and Muslim visions of the World. Both visions tried to control this strategic area. Even in the last years of Tito’s regime, Culture manipulation was a fact. The culture was used as an important dividing force, just in the opposite way as an agglutinating. This instrumentalization, together with religion, was the engine for different mobilizations in the late 80’s.

The Balkans conflict meant the dismantlement of Historical and cultural sites for military or political reasons. Baumel (1993, p. 3) has calculated an eradication of nearly 75% of the common heritage with the consequences of a cultural catastrophe. All the communities involved in the conflict have suffered irreparable damage in many ways.

The priority of some International Institutions was the recomposition of these destroyed Heritage-scapes, as a way of contributing to peacebuilding efforts in the region. Two interventions during these post-conflict years illustrate the feelings and intentions of the several communities: Halbwachs (1992, p. 222) confirms the inexistence of specific signs as symbols in the landscape and the needs to recompose this fact: ‘A society, first of all, needs to find landmarks....it is necessary that those sites most charged with religious significance stand out against all others’.

Dalmatian Bishop His Grace Fotije , when interviewed on 4 October 2002, clearly defined the intentions of recomposing the heritage as the way to keep memories of previous existences: ‘At this moment, the immense effort is not only the fact that we try to preserve our sanctuaries and a small number of people in Orthodox faith but also the evidence that we exist in this region’.

After the Balkans conflict, the scission of Kosovo from Serbia was a fact. Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) played as a warrantor of the rights for the Kosovo Albanian communities through terror and violence. The result was an important break between Serbian and Albanian communities sharing this territory. Serbian groups were transformed into a minority and Kosovo concentrated in two blocks, one at the north, close to the Serbian frontier and the other one around Prizren. The UN Security Council Resolution 1244 established the status of international administration to govern the region (the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo, UNMIK), and NATO peace-keeping forces (KFOR) were called to keep peace and stability in Kosovo. Currently, KFOR continues to be present in Kosovo meanwhile a Kosovar government is assessed by diverse European Institutions to warranty the normal administrative process.

In 1999 the Serbian Orthodox Church published “Crucified Kosovo”. It is a booklet that affirmed the number of 76 religious places destroyed during the summer of that year. Similar actions were reported since at least 200 of 600 mosques in Kosovo were previously destroyed. Both facts provoked a debate on the reconstruction of religious heritage monuments. KFOR troops were appointed to protect the religious heritage buildings, but after 1999 the cleansing progress even grows up.

UNESCO Venice office published a report through its webpage considering that the sad process in Kosovo “… was not only monuments but also memory and cultural identity that were being destroyed’. An effort from several countries, International Institutions and NGO, led to the reconstruction or restoration of forty-eight Orthodox and fourteen Islamic religious buildings. In the last 15 years, the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA) supported efforts of reconstruction of Mosques and Hammams in Kosovo, as well as in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Relations between Belgrade and Ankara were affected by these supports. The Council of Europe assessed the Kosovar government to promulgate a Law on Cultural Heritage (2006) and the National Strategy for Cultural Heritage 2017-2027. This strategy faces the general framework for the coming years, with objectives spread in the following main topics:

-

Structuration of the legal and institutional framework.

-

A comprehensive vision of the cultural heritage and its promotion, through sustainable development.

-

Understanding cultural heritage as a basic element for future strategic national development plans.

-

Education, promotion training, and active participation in the protection of cultural heritage.

Regarding topic 3 the Law defines a specific compromise. Basically, the document calls for the need for education, promotion, and continuous citizen awareness about the trauma scenario. The document continues calling for focusing the efforts on the role of cultural heritage to foster the sense of cultural identity and background, promotion, and facilitation of inter-cultural and inter-religious dialogues. The last objective would be for Heritage to become a source of inspiration and innovation for future generations.

Regarding the last topic, four objectives are defined to improve the “access to all” to the cultural heritage: 1- The Promotion of the National Strategy for Cultural Heritage, to strengthen the public debate and awareness relating to the objectives of the National Strategy. 2- Improving intellectual, physical, and virtual access to assets and locations of cultural heritage. 3- Promotion of alternate uses of heritage sites, with a purpose to strengthen the link between cultural heritage and arts. 4- Promotion of traditional knowledge transfer of collective memory and spoken histories from the older generation to the new generation.

Currently, the most important intercommunal Heritage problem is referred to as the crash provoked by the tentative reconstruction of an old church in a Monastery that is considered by the Kosovar Government as an archaeological site.

The dilemma they are dealing with at this moment is based on these questions:

Is it adequate to act over archaeological sites, and how?

Is it ethically approved the presence of the Serbian Orthodox Church using spaces considered today with special protections and archaeological sites? Which is the prevalence of historical uses or functions over the current statement of the country?

Which function must prevail over the second one: religious or cultural? Maybe none of them?

Coming back to a wider perspective:

Which is the role played by built remains, practices and discourses of the past play in the demarcation and branding of urban territories?

Which are the consequences of the displacement/ replacement of heritage elements referred by such a social group by the opposite group?

How do the Interpretations and Presentations of Cultural Heritage Sites clash today with the religious functions performed in such spaces?

Which principles should prevail to define the adequation of the technical means and methods when used in cultural and heritage contexts?

As partial conclusions, we can agree that the reconstruction of cultural heritage in post-trauma scenarios becomes a matter with political nuances, either based on domestic or international levels. In both cases, the respective identities had been contested and their symbols had been deliberately destroyed in post-conflict societies (Teijgeler & Stone, 2011).

4. Heritage as a tool for the territorial and social recomposition

Facing the previous problems and specific cases presented, where the heritage is used as a tool for mismatch, Heritage can play an important role for territorial and social recomposition.

Francophone studies assume the term “patrimonialization”, to refer to the historically situated projects and procedures that transform places, people, practices and artefacts into a heritage to be protected, exhibited and highlighted (Gillot et al., 2013). “Patrimonialization” from an ethnological perspective would become an analytical tool used for the processes in which objects and social practices acquire the rank of heritage. From a geographical perspective, the same term is used to research and act on the construction of territories. (Herzog, 2011).

The heritagization can be susceptible to being used as a new way of colonialism, sometimes hidden within a globalization process. So the last goal will be always to avoid considering Heritagization as a confrontational arena were different categories of actors compete to impose their rights and/or identities (El-Haj, 2008; Maeir, 2004). The relation between heritage and their respective hinterlands is vital to understanding the composition of Heritage-scapes. They are the scenarios where heritage is strongly preferred to the place and where territories play an important role.

Spirits of conflict territories are reflected in their own Heritage spaces. There is a strong interaction among them. They contribute to emphasizing the breakdown of relations between opposite social groups that share the same territory. This consideration let us develop the idea of using Heritage as an opportunity for these spaces to be a reference for the reconstruction of the interrupted links among several communities. Memories and identities almost fulfil the scenarios where Heritage is flowing in any of the meanings of this term. Hajrullah Ceku (Cited in Avdyli, 2017), a member of NGO EC Ma Ndryshe, resumes these kinds of relations:

“Memory is what we are. It is a part of our identity. Without memory, we have no identity, and if we preserve our cultural heritage, then we preserve our memory,” … “I’m talking more about local identities, neighbourhood identities, and their preservation. Old buildings are not valuable just because they are old. Their value exists because of the connection that they have with the people around them”. In the case of conflict territories, Heritage must deal with the dispute of territoriality, sovereignty, and issues referred to as cultural cleavages.

Stefan Surlić (2017), confirmed the existence of scenarios where Cultural Heritage stays between Religion and Myth. The historical coexistence of Serbs, as Orthodox Christians, and the Albanians, who are mostly Muslims. Contributed for different myths related to historical rights on the common Kosovar territory were implemented. The Serbian perspective is based on the territoriality of the historical origins of the Serbian national and religious identity. The Albanian territorial vision is focused on the promotion of the recent Kosovar state based on the ‘Albanianess’ (Obućina, 2011). Both myths become integral parts of each coexistent identities. They seem to be the antagonist in the territorial management and clash till the point of trying to get the delegitimization of the rights of the opposite side through denying the right to the cultural heritage to the opponent.

The journalist and philologist Vedran Obućina (2011) remarked on the existence of Serbian and Albanian myths sharing the same territory: The Serbian myth perceives Kosovo as “ the heart and soul of Serbian national and religious identity”. The Albanian myth “uses the history and culture to promote the ‘Albanianess’ of the new Kosovo state”. In a parallel way, the UNESCO and other International Institutions strategies seemed to separate the concepts of national sovereignty and cultural Heritage in this case. There are progressively more voices claiming for such agreement in this conflict territory. Professor Surlić (2017) (from the Faculty of Political Science, University of Belgrade) concludes that cultural sites must be understood as a property of all human beings and the international level of its protection prevail over any local sovereign authority if they are threatened. In this case, both communities should find a balanced agreement on this matter through the separation between the cultural heritage from the assigned political dimension. This fact would create the conditions for the cultural diversity in Kosovo to be an additional element of heterogeneity, fragmentation and incoherence in the Balkans.”

Territorial cohesion, within an accepted diversity, could be achieved if we see Heritage with the feeling of belonging, of community, with social cohesion, but also with sustainable development, that is, with taking care of existing resources, not destroying and squandering them.

It seems to be a consensus on the idea of Cultural Heritage accepting always other perspectives, where its role is important and cannot be postponed: the capacity to communicate, to present and to be an important social-economic resource.

5. The definition of the action model on heritage in conflict territories

Most of the regional societal conflicts involve ethnic societies. Consequently, the respective identities (supported by the Heritage manifestations) are within these conflicts as an inseparable part of the conflict. Based on previous experiences presented in this paper, a definition of action modes over conflict territories concerning the Heritage field is needed. There are common points revealed as social mood patterns that must be observed:

- All the parties involved in the conflict see Heritage in a partial way. In the initial post-trauma moments, an impartial vision from both parties is not possible.

- Own heritage elements are used as the way to improve nationalism and reinforce the own identity

- At the same time, the heritage elements of the other disputing party are conceived as the way to perpetuate the presence/ dominance of the enemy in the own country.

- The third way, promoting the reconciliation path, is a long process with extreme difficulties during the first conflict generation

- International arbitrations play an important role on site since they try to be warranties for Heritage preservation as well as channelers of the positive actions over it.

- A first step for the use of the heritage elements as tools for the social recomposition always needs strong support for these International impartial Institutions.

- The less allocation of political content the patrimonial elements have, the better and faster territorial and social recomposition will be achieved. It is the moment where Heritage must be considered as a challenge for opposite social groups, as a part of shared memory.

- Urban Heritage must play an important role to mediate socio-spatial discrimination and exclusion. The urban landscape layouts of the cities strongly support this point since landscapes must reflect these sharing spaces.

Arbitrations of the International impartial Institutions play an important role in all these different processes. In the beginning, a learning process of shared responsibilities on a coexistent Heritage is only possible under its coordination. Master plans for recovering diverse heritage elements, preferably in an equal number of them in the macroscale, should be coordinated. In any case, a specific master action plan for recomposing heritage scenarios from a multilayer perspective should be coordinated, too. This master action plan would assume a philosophy based on these topics:

- Main functions on the place, from both parties, would be always shared without special prevalence.

- The mutual respect of several functions, spaces, ideas, and beliefs must be kept.

- The definition of mechanisms to warranty free mobility and accessibility to the place

- The definition of internal rules distributing direct and shared responsibilities on the place, under the auspices of International Institutions

- Principles of sustainable tourism on heritage spaces must be kept too, as the way to avoid an introspective situation, opening the spaces and the country to external visits.

6. Conclusions

Different conclusions, able to be extrapolated to other similar case studies, can be taken into consideration:

- Heritage has a double role in conflict territories, as an engine for the recomposition of regions and as a victim of the actions related to the social conflict.

- The way how Heritage will be conceived in such conflict territory will strongly depend on the capability of the implied stakeholders to divert the actions positively, through the redirection of the different actions.

- Interactions among components of the social and cultural complexity of civil conflicts can be important troubles for the previous reconciliation actions.

- Heritage can be considered an object for the conciliation under the premise of being the will to reconstruct physical spaces, where both parts can conceive the same space from different perspectives.

- Roles of the International Institutions are essential to achieve the adequate climate for developing the territorial and social recomposition, where Heritage plays an important role. The more implication of the political aspects within other fields, the more difficult and limited results of these actions.

- The roles of the NGOs are important stakeholders of the process because of two reasons: they can arrive where International Institutions cannot or must not get, and they have a bigger capacity for closer interaction in different social groups.

- Independent assessments and coordination of the recovering heritage actions are vital for having successful results. In this case, the profile of these assessors must be carefully selected to avoid rejection by any of the litigants in the conflict.

Future research lines must be based on specific cases where the interaction between International Institutions and NGOs must be clearly defined on specific procedures for each case. Since the last elections in 2020/2021, some changes happened in both conflict territories. New presidents of Kosovo and the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus have drawn new geostrategic scenarios, where eventual changes in the way of conceiving the respective Heritage roles must shortly arise. Hopefully, the routes to be taken will be in the future will support the ideas of reconciliation, using the Heritage as an effective strategy for recomposing territories.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Andrieux, J.-Y. (2016). Heritage and War (20th-21st centuries). “From mass destruction to deliberate demolition of monuments”.”Le patrimoine et la guerre (XXe -XXIe siècles). De la disparition massive à la destruction intentionnelle des monuments”. What Does Heritage Change,P. 87.

Avdyli, N. (2017). Why should we protect our cultural heritage? Kosovo 2.0. https://kosovotwopointzero.com/en/pse-duhet-mbrojtur-trashegimine-kulturore/

Baumel, J. (1993). The destruction by war of the cultural heritage in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina presented by the Committee on Culture and Education. http://www.assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=6787&lang=en

Berisha, M. (2012). Archaeological Guide of Kosovo (L. Kemajl & E. Rexha (eds.)). Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport.

Constantinou, C. M., & Hatay, M. (2010). Cyprus, ethnic conflict and conflicted heritage. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(9), 1600–1619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419871003671937

Di Pietro, L., Mugion, R. G., & Renzi, M. F. (2018). Heritage and identity: technology, values and visitor experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 13(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2017.1384478

El-Haj, N. A. (2008). Facts on the ground: Archaeological practice and territorial self-fashioning in Israeli society. University of Chicago Press.

Giblin, J. D. (2014). Post-conflict heritage: symbolic healing and cultural renewal. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20(5), 500–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.772912

Gillot, L., Maffi, I., & Trémon, A. C. (2013). “Heritage-scape” or “Heritage-scapes”? Critical Considerations on a Concept/«Paysage patrimonial» ou «paysages patrimoniaux»?: réflexion sur l’usage d’un concept, Ethnologies, 35(2), 3-29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1026546ar

González, M. V. (2008). Intangible heritage tourism and identity. Tourism Management, 29(4), 807–810. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.003

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On collective memory. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226774497.001.0001

Hutchings, R. M., & Dent, J. (2017). Archaeology and the Late Modern State: Introduction to the Special Issue. Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress, 13(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/DOI 10.1007/s11759-017-9311-0

Informal Meeting of ministers responsible for Urban development. (2007). Leipzig Charter on sustainable European cities.

Legnér, M. (2018). Post-conflict reconstruction and the heritage process. Journal of Architectural Conservation, 24(2), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2018.1463663

Maeir, A. M. (2004). Nadia Abu el‐Haj. Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self‐Fashioning in Israeli Society . xi + 352 pp., illus., index. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. $20. Isis, 95(3). https://doi.org/10.1086/429039

Obućina, V. (2011). A War of Myths: Creation of the Founding Myth of Kosovo Albanians. Suvremene Teme, 1(4), 30–44. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=14400

Pavlović, J. (2017). Serbian Monumental Heritage in Kosovo and Metohiјa in View of Contemporary Cultural Heritage Theories. In D. Otašević, M. Marković, & D. Vojvodić (Eds.), Serbian Artistic Heritage in Kosovo and Metohija: identity, significance, vulnerability (pp. 80–82). SASA.

Surlić, S. (2017). Constitutional Design and Cultural Cleavage: UNESCO and the Struggle for Cultural Heritage in Kosovo. Croatian Political Science Review, 54(4), 109–125. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=672881

Teijgeler, R., & Stone, P. G. (2011). Archaeologist under pressure: neutral or cooperative in wartime. Cultural heritage, ethics and the military (P. Stone (ed.)). The Boydell Press.