1. Introduction

This study emphases on one of the long-standing questions in the arena of urban design: “Does the urban form influence the aesthetic understanding of it?”. Traditional medieval spatial organization of European cities is the example of good quality of space organization which many scholars have been studied to take out the aesthetic factors of shaping good quality of urban spaces in traditional countries (Cullen, 1996; Sitte, 1888; Krier, 1889; Zucker, 1959).

As a big umbrella for this study the environmental aesthetic have been selected from the literature by focusing on the interrelation between principals of spatial configuration and human aesthetic perception.

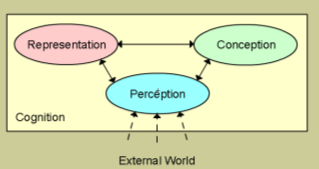

According to Cuthbert (2006) “an aesthetically pleasing experience is one that provides pleasurable sensory experiences, a pleasing perceptual structure and pleasurable symbolic associations”. This description delivers a valuable guide as to the diverse stages of aesthetic perception that are essential to be able to judge an art object or urban spatial configuration. Williams (1996) depicts three interactive elements in the cognitive processes which are representation, perception, conception.

The process of cognition is characterized as the formulation of sensory information obtained from the real world. When sensory information from the world imposes us, cognitive processes at the perceptual level attempt to explicate and understand it (Williams, 1996).

Figure 1. Idealized model of cognition - cognitive processing (Adopted from Williams, 1996).

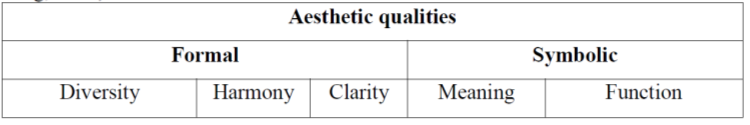

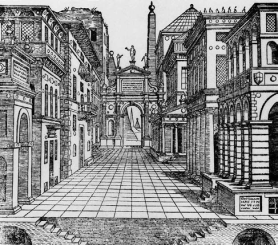

Lang (1988) divided the aesthetic assessment of space configuration into formal and symbolic aesthetic. Symbolic aesthetic represent meaning which has been hidden in an art object or space organization the symbolic object might also be a doorknob or even a tapering stone pillar so called “Obelisk” in ancient Egyptians era. Symbolic aesthetic in a specific culture might have aesthetic value and in the other culture which doesn’t have historical roots might not have. Formal factors representing aesthetic quality refers to the organization and spatial configuration of the elements of shaping urban spaces. The three most important formal factors affecting judgment are diversity, harmony and clarity that tends toward complexity and ambiguity (Nasar 1994).

Table 1. Grouping of aesthetic qualities.

This study will assess the formal aesthetic qualities in shaping aesthetic urban environments. In this regard, Gestalt psychology will helps to comprehend the distinctive human aesthetic taste to resolve visual objects into ordered patterns. Coherence, unity in variety, patterns in building facades and strong compositional elements such as verandahs are but some of the formal characteristics that can enhance a sense of order in a scene. The indispensable parts of the “Gestalt psychology” is connected with urban context. Gestalt psychology developed a systematic basis for aesthetics (Gibson, 1979) which explains the relationship between whole and the parts.

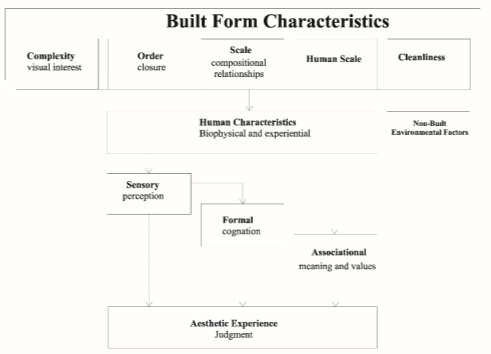

According to Nasar (1994), human response to the quality of the environment will generate a positive aesthetic experience until reaching a level where preference begins to reduce. In this regard, Stamps (2000) states that the built environment provides stimulation of interest at three scales, which are a). Conceptualized as a silhouette (complexity of the outline). b) Form articulation (three dimensional modelling) and c). Surface texture.

Personal experience is also an important factor in generating environmental stimuli. In this regard, as Weber (1995) stated, cognitive processes by assigning values to the derived meanings, helps to understand the environment and affect aesthetic judgments. Accordingly, understanding how this process working with each other will help us to assess the beauty of each and every context.

“Powerful meanings attach to the way we comprehend the environment. Not only do people assess the nature of the activities they understand to take place within, they are also influenced by the degree to which they can imagine themselves able to participate in those activities”. Subsequently, public buildings can have positive “associational meanings” for people of a society. As Alcock (1993) stated standard of construction, maintenance and standard of detailing can carry messages about the status, owner or the way a building would feel to be inside. Considering above mentioned literature in the field of environmental aesthetic, the following analytical framework is derived.

Figure 2. An analytical framework of environmental aesthetics (Adopted from Gjerde, 2010).

According to Figure 2 aesthetic experience or judgment of environmental configuration shapes based on immediate sensory and cognitive appraisal of the scene or object and alignment with schema which formed through experience and appraisal based on meanings and value.

2. The Aesthetic Values

According to Maslow’s Human needs, the need for aesthetic is one of the human’s essential needs to survive. Aesthetic lids to fulfil the physiological requirements to appreciate the presence. In this regard, beauty can be described as human response to the environment with enjoyment and pleasure.

Webster Dictionary describes aesthetic as a branch of philosophy dealing with “the nature of beauty, art, and taste and with the creation and appreciation of beauty” (Webster, 2016). Oxford Dictionary also defined the meaning of the word aesthetics as "knowledge derived from the senses ". As it comes from the definition, aesthetics are associated to perception by the “senses”. According to Lang(1987) the knowledge of aesthetics is concerned with understanding and identifying the aspects that contribute to the perception of an object and understanding the nature of human ability to enjoy creating presentations that are aesthetically attractive (Lang, 1987).

“The aesthetic judgment is concerned with all emotions, feelings and senses in one moment, and has an association with “physical actions”. Therefore, aesthetic judgments are subject to cultural condition in some areas. The decisions on aesthetic value can be related to moral, economic and political values and also in terms of relying on feelings: emotions, mental, intellectual, views, preference, behavior of non-conscious, conscious decision, training, instinct and social logic are the other aesthetic factors which human might think aesthetically by relying on the feeling (Hussein, 2009). Many traditional signs and symbols are considered to be creative connotations that signify the experience and originality which are based on the magnificence of the past(Arenibafo, 2016; Hariry, 2017). Overall, it can be concluded that the aesthetic value of a specific culture might be different than the other cultures and it might be varied by considering different social political and environmental variables which have different effects on human taste.

3. The Aesthetics of the City

Urban aesthetic is a tool for city identification; it is an indispensable element in the urban dynamics (Sternberg, 1991:78). To consider a city beautiful, not only judging its architectural style, buildings, traffic and their noise effects, but also social and historical features (as part of its total sensory package) should take into account in the assessment. Despite the fact that some scholars put forward that increasing the aesthetic qualities of cities affects on its appreciation, others scholars claim that “appreciation” is itself a challenging notion. Because it is vague and hard to define and justify. The query of “what it means to appreciate a city” is indeed one of the difficult tasks of urban aesthetic design.

According to Jackson (1959) social - economic efficiency, biological and health are the major goals in designing the city. He revealed that cities should provide for their citizens aesthetic experience. This is a responsibility of urban designer in city scale and citizen in the scale of house by design the houses in human scale. The aesthetic of the city is not a one day job to fulfil all the requirements of its citizens, it might take centuries of try and fail. That’s why as Mumford (1966) stated, “cities considered as the greatest artwork of human history, which buildings can be considered as a work of art”.

According to Blanc (2013) “… giving the urban setting its full meaning requires aesthetic engagement which involves a visual learning experience from the natural, physical and emotional dimensions as the aesthetic experience is not related only to building environment but it also comprises the living environments”

Indeed, urban aesthetic reached its highest level in traditional European cities. The cities have been designed in such way that to fulfil all the human needs, considered as designing based on human scale. As Rossi (1988) stated, architecture is an inseparable form of urban aesthetic to be able to live with pleasure in the context.

In his documentary movie with the name of “The social life of small urban spaces” William H. Whyte (1979) sums up the attributes and qualities that make a public space successful. These qualities are suitable space, street, sun, food, water, trees and triangulation (Whyte, 1979, 42:34). These attributes refer not only to the physical environment and design of the space, but also to the sense of community and the everyday interactions. Following William H. Whyte’s perception of the attributes of public space and what makes a successful site, the non-profit organization “Project for Public Spaces” (2012) created a tool or a kind of “protocol” that would assist in the identification and evaluation of those attributes. This “protocol” has given the main guidelines in order to form the research questions of the thesis. The Place Diagram has developed based on the Project for Public Spaces (2012) which was an attempt to identify those attributes that make a place aesthetically successful-by fulfilling all human needs (Project for Public Spaces, 2012). The criteria, the four attributes stated in the figure 3 are the four qualities of space that are used in this research. Comfort, Sociability (stated as Sense of Community and Sociability in the research), Access and Linkages (Accessibility in the thesis) and Uses and Activities are the four “key qualities” of place under investigation. These qualities tries to satisfy human needs in the place and consequently the responds of the users will lead to aesthetically appreciate the place.

Figure 3. The Place Diagram, developed in the Project for Public Spaces (2012).

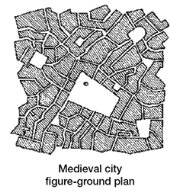

It is revealed through this study that aesthetic experience laid down in the cities and it needs moving to explore. Traditional European cities due to its specific medieval alleys have the potential to reveal one specific vista of the city and this sense of aesthetic exploration increase pleasure and satisfaction. Experience of moving, dynamic vision and the sequential rhythm or serial vision is the most important aesthetic characteristics of traditional European cities.

“Since the establishment of the urban landscape is the art of the relationship, and the most important approach in the aesthetic design of the cities is the art of forming. Urban designers are dealing with aesthetics as visual forming similar to the works of art and considered the essence of success which is the sense of unity associated with clarity”. (Porteous, 2003)

According to Cullen (1961), “the buildings that are seen collectively give visual pleasure which cannot be given by each building separately. The building, which stands alone called architecture, but a set of buildings together is an art of forming”. Cullen stated that “the cityscape cannot be evaluated technically, but as an art of relationships that need to be aesthetic and visual sensor” (Cullen, 1961). In his book “The Concise Townscape”, Cullen (1961) revealed some basic characteristics which have already been developed in European traditional cities which are:

Table 2. Basic principles of aesthetic space organization.

|

Serial vision |

-Exploring the urban aesthetic by moving. - The serial vision of the urban landscape elements as a whole. |

|

The sense of place |

-The sense of place that determines the sense of the individual in the environment. |

|

Visual permeability |

- The urban content of the scene like color, texture, scale, style, character and uniqueness, as the aesthetic value of urban space determined by the properties of visual sources.

|

|

Topographical components |

-Linked to the aesthetic values of natural components which reflects the richness of the urban environment, and natural values of high aesthetic properties |

4. Aesthetic Qualities of traditional European urban squares

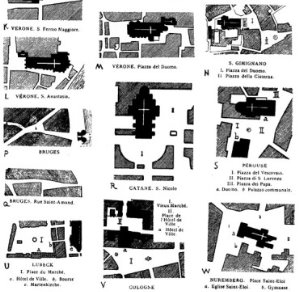

Through the literature of aesthetic urban spaces, urban squares by considering the proportion of depth to width and their degree of proximity are classified into groups based on their ground form and morphology. Many studies developed typologies of squares through the literature. The most important of them undertaken by Sitte (1889), Stubben (1924), Léon and Rob Krier (1975), Zucker (1959) and Ashihara (1983). Differences in the classification vary depending on the distribution of public buildings, form and proportions.

Figure 4. Camillo sitte and the organization of public buildings around the squares.

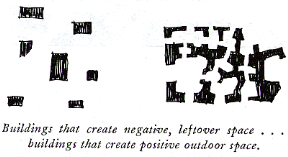

By considering sitte’s analysis of public open spaces, it’s obvious to see that urban space getting its quality based on the organization of its objective space. Building organized in such a way that to crease sense of enclosure which leads to positive spaces. In this regard, Alexander (1980) in his book the pattern langue state that “When assessing the quality of a square or urban space it is particularly interesting to note that certain spatial configurations have a similarly positive or negative effect on their users”.

Figure. 5. Building integration in creation of negative space and positive outdoor space. (Alexander et all 1980 p518)

Based on Sitte’s analysis (1989), traditional European cities have been developed its knowledge of space organization. Spaces have been designed in such a way that to increase sense of human pleasure which leads to aesthetic satisfaction. Designing positive spaces by enclosures is a method of creating a pleasurable public open space. Understanding this rule of space organization in designing contemporary urban spaces is the missing point which highly required to pay attention in the design process.

5. Indicators of aesthetic space organization

There are many indicators for the quality of an urban square organization. Together they cover three different scales and all aspects of life in a square: a). At the micro scale, its spatial elements and their respective configuration and emotional impact on the user. b). At the meso scale, its vitality and communicative potential c). At the macro scale, the integration of the square into the structure of the city and the quarter,

Each of these three scales of analysis has four quality indicators. Which are 1). Integration 2). Vitality. 3). Spatial quality. At the macro scale the category “integration” describes in essence the context and the degree of connectivity a space has with its context. Traditional European cities have been developed the level of integration in highest as it possible. From the other hand, at the meso scale vitality aimed to develop the communicative potential of urban spaces. Vitality has direct relation with livability. In this regard applying all the methods of converting public spaces to livable place such as mixed use function will lead to increase vitality. Finally, the category “spatial quality” at the micro scale describes those properties that affect our perception of a space and how we experience its spatial qualities.

5.1. Integration

The term integration derives from the Latin word “integration” which means the creation of a whole. In an urban space “to be properly part of a whole, it needs to have a high degree of integration”. This means that it must be mainly firmly intertwined with its close contest. The four indicators defining this category are Mobility, Connectivity, Access and Spatial System.

Figure 6. Space integration representing Mobility, Connectivity, Access and Spatial System.

5.2. Visual connectivity

The visual connectivity of a space with its environs through sight lines is what Cullen (1996) describes as what constitutes a “sense of here and there” which leads to help its user to find a logical connection between space organization with the feeling of self. This helps to its user’s to grow a comprehensible “mental map”. According to Cullen access is undoubtedly is the most important of the four indicators defining this category.

Figure 7. Serial vision as a method of assessing special connectivity. (Cullen, 1961)

5.3. Vitality

The factors that have the biggest impact on the vitality of a square describe the elements that influence social interactions and the kind of ways in which the space is appropriated by its users. The key indicators are Inward Focus, Dialogue, Character, and Security.

Figure 8. Vitality as one of the main factors shaping special quality.

The orientation of the objective elements of urban spaces is the most important factor in developing vitality in space organization. According to Gehl (2010) “The Dialogue between the user and the space is mediated by the orientation, design and functions contained within the buildings that surround a public space”. Generally speaking, facilities and buildings that willingly permitted in the public realm to extend into their privately-owned spaces contribute to the vitality of an urban space.

Sense of security is another factor which leads to the vitality of urban spaces. When people of a city feel a sense of security they will participate in the daily activities of urban spaces, this kind of participation which might encompass different people from different culture and background will increase the livability and at the end the vitality of urban spaces.

As it is already mentioned, positive enclosure which will leads to increase the viability of urban spaces is another factor which will lead to increase sense of security.

Jane Jacobs in her book “the death and life of great American cities” revealed that designing a buildings in such a way to increase the number of opening from the buildings to the public spaces will increase the séance of security “… Residential apartments with windows overlooking public spaces, and cafés and shops that face public spaces make it possible for see what goes on in the public space and provide a level of social control, in turn heightening the actual and perceived sense of security”. (Jacobs, 1961)

Figure 9. Corso Vannucci, Perugia.

5.4. Spatial Quality

All the objective elements composing the public spaces participating in the aesthetic representation of all the spaces, and urban squares in particular, is defined to a large degree by water, trees, walls, texture, floor and any objects that may be in the space. The way which it needs to be organized the objective elements is also affected in increasing the spatial quality of spaces. Even while the shadow of the building is moving through the day is also affects in spatial quality of the spaces.

Figure 10. Objective organization of space elements affects on spatial quality.

“These elements do not themselves describe the quality of a space, but each element, through its constitution, size and proportion, position in space and by relationship to other elements of urban spaces influence the quality of the urban space”. They make atmospheric and spatial qualities through their composition and elaboration in terms of topography, scale, access, figure, position and formation as well as their mutual interrelationships which will have a significant effect on the overall spatial and atmospheric quality of the space.

According to Ashihara (1983) “The boundaries that surround a space, not just the walls but also facades / Floor surfacing that extends to a boundary and makes the extents of spaces legible / Inside corners that define the sense of enclosure / harmony and unity, and of the buildings that surround the space / A balanced association among the height of the surrounding walls and the distance between them, constitutes an urban space with the spatial qualities” (Ashihara 1983).

Figure 11. Objective elements of the space representing spatial quality (Moughtin, 1992).

Overall, urban spaces are deemed good quality if it by providing pleasant condition both from an objective space organization based on human scale and subjective symbolic quality of space organization. The amalgamation of objective and subjective elements of urban space organization might lead to pleasant condition. Spatial qualities in urban spaces can be labelled by three indicators: 1). Centrality, 2). Directionality and 3). Enclosure.

1. Centrality in urban spaces is spatial quality which generally developed based on the organization of the objective elements of the urban spatial configuration. As Zucker (1959) stated Centrality is perhaps the most elementary form of European squares that defines the significance of the enclosure.

Figure 12. Centrality representing spatial quality. Example St Peter’s, Rome.

2. Directionality is another factor in space in space quality. Meaning that objective elements of urban space organization have been designed in such a way that to highlight on specific events or art object at the end of its own direction. Lynch (1960) called this sense of directionality as “channel” which is one of the most important indicators of imageability in urban spaces. Directionality can also be shaped by the repetition of specific shape or object in one specific axes.

Directionality will also increase the pleasures of exploring the spaces. In most of traditional European cities directionality in alleys leads to public space or a specific public landmark.

Figure 13. Directionality representing spatial quality.

3. Enclosure which is the result of enclosing surfaces in public urban spaces can be applied by organization of the objective elements of urban space configuration with the aim of centrality and increasing the sense of security and quality of urban spaces. Lynch (1960) describes Enclosure as “as an area that is separate from others and with its own character.”

6. Conclusions

It has been revealed thought this study that urban spatial organization in European traditional cities have been developed throughout the history and enriched its aesthetic values by considering and fulfilling all the requirements of its users. In despite of the fact that human scale in design and designing based on human taste and requirement are the most important factor in increasing aesthetic appreciation, there are other factors such as: integration, visual quality, vitality and spatial quality.

The study also revealed that aesthetic values in an urban space organization have direct relation with quality in terms of fulfilling all the basic humans’ needs of its users. The study also revealed that the experience of moving, dynamic vision and the sequential rhythm or serial vision are the most important aesthetic characteristics of traditional European cities. As it has been already mentioned Maslow’s hierarchy define this human needs which have been starts from a need for food to survive till aesthetic needs. European cities through the process of the development of the cities have been fulfilled all the requirements of its users. It has also revealed that serial vision, the sense of place, visual permeability and topographical components are the Basic principles of aesthetic space organization. The study of the symbolic aesthetic of urban spaces in European cities have been proposed as future study in this research.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Reference:

Abdullah, I. H. (2009). Aesthetic theory in the art of design. Modern Discussion, no.2677, (reference in Arabic). Available: http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=175060

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1980). A pattern language: towns, buildings, construction. New York: Oxford University. Available at: http://library.uniteddiversity.coop/Ecological_Building/A_Pattern_Language.pdf

Al-Jaf, A.I. (2008). Aesthetic- from the source of the modern English and French literature of Art in 2008”, Gilgamish Center for Kurdish Studies and Research, 2012, ,( reference in Arabic), http://www.gilgamish.org/viewarticle.php?id=studies-20120316-25994

Ashihara, Y. (1983). The aesthetic Townscape. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT-Pr. https://www.amazon.com/Aesthetic-Townscape-Yoshinobu-Ashihara/dp/0262010690

Atfeh, N. (2008). Modern Policies and Trends in Architecture and Contemporary Cities. Presented at the Workshop-atelier/terrain – Jinze (Qingpu-Shanghai) p.13-14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311583763_Aesthetic_values_of_the_future_cities

Arenibafo, F. (2017). The Transformation of Aesthetics in Architecture from Traditional to Modern Architecture: A case study of the Yoruba (southwestern) region of Nigeria. Contemporary Urban Affairs (JCUA), 1(1), 35-44. https://doi.org/10.25034/1761.1(1)35-44

Blanc, N. (2013). Aesthetic Engagement in the City. Contemporary Aesthetics (CA) online journal, Volume 11 (2013), p.2, http://www.contempaesthetics.org

Cullen, G. (1961).The Concise Townscape. The Architectural Press, London, 1961, p.147. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10834661

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Washington, DC: Island Press. http://www.sfu.ca/~paulb/iat233/Cities%20for%20People(ch1-2)_Jan_Gehl.pdf

Gibson, J.J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston:Houghton Mifflin Company. https://daughtersofchaos.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/gibson_occluding-edge_1979.pdf

Hariry, Z. (2017). The Influence of Globalization on Distracting Traditional Aesthetic Values in Old Town of Erbil. Contemporary Urban Affairs (JCUA), 1(1), 56-66. https://doi.org/10.25034/1761.1(1)56-66

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House. https://www.buurtwijs.nl/sites/default/files/buurtwijs/bestanden/jane_jacobs_the_death_and_life_of_great_american.pdf

Lang, J. (1987). Creating architectural theory: role pf the behavior science in environmental design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1154&context=jstae

Lang, J. (1988). Environmental Aesthetics: Theory, Research and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/tr/academic/subjects/psychology/social-psychology/environmental-aesthetics-theory-research-and-application?format=PB

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge, England: MIT Press. http://www.miguelangelmartinez.net/IMG/pdf/1960_Kevin_Lynch_The_Image_of_The_City_book.pdf

Moughtin, C. (1992). Urban Design Street and Square .Oxford: Butterworth Architecture. http://www.cmecc.com/uploads/%E8%AF%BE%E6%9C%AC%E5%92%8C%E8%AE%BA%E6%96%87/[76][%E8%A7%84%E5%88%92%E8%AE%BE%E8%AE%A1]Cliff.Moughtin(2003).Urban.design_street.and.square.pdf

Mumford, L. (1968). City: Forms and Functions. in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan Co. and the Free Press. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/journalcpij/43.3/0/43.3_157/_article/-char/en

Porteous, J.D. (2003). Environmental Aesthetic: ideas, politics and planning, Taylor & Francis e-Library, London and New York. p.22. https://epdf.tips/environmental-aesthetics-ideas-politics-and-planning.html

Rossi, A. (1988). Architecture of the city. MIT press. https://monoskop.org/images/1/16/Rossi_Aldo_The_Architecture_of_the_City_1982_OCR_parts_missing.pdf

Simpson, J., & Weiner, E. (2012). Aesthetics. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/aesthetic

Sitte, C. (1889). City Planning According to Artistic Principles. (G. R. Collins, & C. Collins, trans.). London: Phaidon Press. https://www.amazon.com/City-planning-according-artistic-principles/dp/B001O2HYFM

Whyte, W. H. (2007). “Introduction”, “The Life of Plazas,” “Sitting Space” and “Sun, Wind, Trees, & Water.” In M. Larice and E. Macdonald (Eds.), The urban design reader (pp. 348-363). London, England: Routledge.

Williams, S. F. (1977). Subjectivity, expression, and privacy: Problems of aesthetic regulation. Minnesota Law Review 62(2), 1-58. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/mnlr62&div=10&id=&page=

Wolter, B. (2008). Die Gestalt des öffentlichen Raumes. Stadträume in der ahrnehmung der Nutzer. Available online at http:// www.avbstiftung.de/fileadmin/projekte/LP_AvB_Wolter.pdf , updated on 3/06/2008, checked on 2/12/2011.

Zucker, P. (1959). Town and square form the agora to the village green. New York: Columbia University Pr. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271626032900157

How to Cite

Nia, H., & Suleiman, Y. (2018). Aesthetics of Space Organization: Lessons from Traditional European Cities. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs, 2(1), 66-75. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.3659

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivs 4.0.

"CC-BY-NC-ND"