1. Introduction

The idea that cultural heritage should be considered within the complete landscape that it constitutes a part of has been generating a series of implementations around the Globe. It is the awakening that admits conservation of cultural objects in isolation has a destructive effect for cultural and urban integrity (Turner and Tomer, 2013). Integrity is a key concept which is used to explain the conditions where things are meaningful for those who see, appreciate, and live with them (Ripp and Rodwell, 2016). This appears to be the reasoning behind the HUL approach in which the responsible awareness of the people living in that specific cultural landscape. This study explores the question why and how the interrupted urban integrity can be dangerous for the heritage objects in a cultural landscape on the example of Ankara.

This study explores Ankara’s historic integrity through the final intervention applied in the Hergelen Square through the framework of the HUL approach, and considers its survey outcomes together with a previous survey on the public perception of the heritage value of another historic site in the same district. These two sites have been subject to similar scales of interventions recently that represent a greater scale of transformation together. Given the HUL based role of local communities on urban preservation of a city’s historic integrity, this study is based on the research question that asks whether the social awareness of and responsibility for cultural heritage preservation in the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) of Ankara is affected by major transformative interventions in its historic sites. An indicator for this affection is the responses of the public to these interventions.

On a search for how these interventions are conceived by the public, it is possible to come across with the declarations of academics or institutions representing the experts of urban planning and/or architecture as reactions against the illegality of these interventions, their effects and consequences. On the contrary, a majority of the public press and declarations of local authorities have a completely different discourse about the way they comprehend the transformed environments. Therefore, the polarity in-between these two opposing perceptions makes it necessary to research on the actual comprehension of the public for the causes and effects of these interventions. The public has a shared memory of these sites under transformation embracing their pasts, ongoing transformative interventions that they were subject to and these two opposing perceptions on these interventions. Hence, the current perception of the public may provide an insight about how these interventions might change the way HULs are conceived by the local public.

The questions that arise from this need are threefold. The first asks whether the residents of Ankara valued a former intervention in Hergelen Square as a part of their cultural perception for the city. The second question asks what consequences the former disintegrated solutions have for today’s citizens. And the third one asks whether a comparison of the outcomes of the independent surveys on the public perception of the historicity of two different parts of the HUL of Ankara display a common indication about the effects of interventions in the public awareness for cultural heritage. In order to achieve the required answers, a public survey on the Hergelen (İtfaiye) Square in Ankara was applied based on its shared memory among Ankara’s residents and their conceptions about the recent transformations. The results of the survey were considered together with a previous study on the cult historic site of Hacıbayram Square and the public perception of the recent transformations applied on it.

2. The problem of interrupted urban integrity

Problem of interrupted urban integrity is expressed by Ripp and Rodwell (2016) as the condition of destroyed systemic properties, where the system is divided into isolated objects or concepts. This isolation is a result of leaving the responsibility of having a perception for heritage protection to a very limited community of experts. It also means the dissolution of the links between heritage objects and the contexts that renders them as meaningful parts of an integrated whole. As Ripp and Rodwell (2016) suggest, urban heritage is meaningful by way of its interaction with people and people may not assume responsibility on individual objects of heritage like buildings which do not have a meaningful integration with today’s communities. Inversely, when an object is a meaningful part of the urban landscape, this responsibility reveals public action. As Myolland and Grahn (2012) put it, when the objects of a cultural landscape are not formally listed as heritage, preservation of cultural heritage is often handled by the voluntary actions of the local communities. The role of public on heritage protection is connected with the meaningful integration of the heritage with its community. According to Harvey (2001) heritage is the long term development of its society and it is a societies relationship with its past that determines the focus of what to research on its heritage (Harvey, 2001, p.320). It is explained with the value system of a community, where heritage is the object of which. Especially for today, urban communities are not stable, nor can their value systems be. This has reflections with the cities that the communities interact, and as Bandarin and van Oers (2012) explain the natural change in a city can be through its adaptation to the evolution of social structures and needs which also determine the limits of acceptable change. According to them, the historic city expresses social values that keep the “collective identity and memory, helping to maintain a sense of continuity” (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012).

Van Oers (2010) asserts that the significance attained to cultural heritage is open to change with the diverging multiplicity of the societies, which makes it necessary for the societies to make progressive redefinitions of their value systems, if what they value needs to be protected. The urban disintegration could also be a consequence of the challenges in the global, regional or local scales like demographic changes within the society resulting from migration (Ripp and Rodwell, 2016). As Bandarin and van Oers, (2012) state, in the 20th century, urban community was diversified with the addition of multiple communities, which resulted in a reinterpretation of the values of the historic city. Regarding the management of urban conservation, the authors suggest that, which values to preserve for the integrity of urban landscape should be decided through the collaboration of the communities of users and experts (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012; 68). According to Ripp and Rodwell (2016) the share of responsibility for heritage protection among the experts and local community should be maintained by moderators who follow the changes in what the community values.

3. The HUL approach and community engagement

This is a view shift in the understanding of urban conservation, which also includes the conservation of architectural heritage as part of a complete cultural landscape, predominantly including the active participation of the community for explicating and reinterpreting their transforming value systems. It is the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach, which appears as the most recent form of understanding that has emerged on the perceived need for an urban management, which is truly integrated with the preservation issues (Turner and Tomer, 2013). Accordign to Zeayter and Mansour (2017, 12) the HUL approach is capable of providing awareness of the public for taking part in the management of urban conservation plans. Taylor suggests (2016) that the HUL paradigm is an approach, through which we can see cities as the reflectors of the values and belief systems of their communities.

The HUL approach is based on two important achievements in the definition of the relationship of historicity with the city, by the international community of conservation. One of the origins of the discussion was the decisions adopted by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in 2003 and the other one which proceeded the approach further was the Vienna Memorandum in 2005 (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012). According to Ripp and Rodwell (2016) the first signs of the HUL approach dates back to the 1975 Council of Europe Euroean Charter which was when the integrated conservation came into agenda together with the recognition that architectural heritage should be considered in urban and regional planning. Basically, it is a change in the way conservation is conceived not in isolation with the “objects of the monuments”, but together with the “subjects of the living cities” (Turner and Tomer, 2013).

The goal of the HUL approach has been discussed as achieving sustainable urban environments (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012), but according to Ripp and Rodwell (2016), recently there is a greater emphasis on urban resilience. The authors describe the “systems approach” in which, problems are viewed as parts of a single overall system and not in isolation. As they explain, compared to the sustainability approach, resilience is more complex, more dynamic and requires being flexible to change without leaving the overall system and it can also empower communities (Ripp and Rodwell, 2016).

The HUL identifies the community of an urban cultural landscape as the primary stakeholder and states that their engagement in the management of urban heritage is crucial as they will be affected by that management (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012, 155). As Taylor (2016, 474) states, in the HUL approach, the concern is particularly based on understanding the role of people who live in and experience the urban places, which results in its definition as taking part in the discussions on heritage and participate in the planning and management of the process. On summing up the discussion on how urban heritage should be managed, as one of the five goals of the HUL approach, Bandarin and van Oers (2012, 193) express: “The reinforcement and the empowerment of local communities in identifying and taking part in the preservation of heritage values within an open and democratic process.” As (Turner and Tomer, 2013) express, one important aspect of the definition for the HUL approach is the adoption of historic cities as a layered structure of a diversity of cultural expressions. Regarding the problem of the multiplicity of values which may have conflicting consequences, this diversity may be a consequence of a divergent society as that of Ankara, in which people from very different backgrounds need their representation to generate values for the cultural landscape.

4. Disintegration in Hergelen Square

Hergelen square has a disconnected memory resulting from different interventions taking place in time. Currently it has a disintegrated character interrupted by the traces and/or effects of these interventions. Before explaining and discussing the results of the survey carried out in order to understand the community’s value system and how they conceive the integrity of the site, this section of the article focuses on its definers and discusses the reasons behind their failure in defining it.

Hergelen Square has a special place in the urban memory of Ankara, which is visible in the novels the stories of which are taking place in Ankara like Oğuz Atay’s The Disconnected (2017) (Tutunamayanlar), where you can read that the name of the square was Opera Square back then. The reason for this is that its place was designed in the Jansen Plan of Ankara (1935) for an opera building that has never been built (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Partial view from the Jansen Plan (1932), taken from Sözen, M. (1984).

The square was defined especially with the eastern entrance of the Gençlik Park, planned as a significant cultural spot on the Atatürk Boulevard, the main north-south axis of the city which is connecting the historic citadel on the north end and presidents mansion on the south end. On that main axis, the eastern boundary of the huge urban park was defined with the exhibition hall, which is currently the opera building, facing the headquarters of the Bank of Municipalities on the opposite side of the boulevard, right next to the place that was formerly called Opera Square and lately called Hergelen Square. As Yılmaz (2006) states, the Exhibition Hall, represented the achievements of the new Republic, which means that the gate of the Gençlik Park on the right side of the exhibition hall had a specific importance. On the East end of the square there is the registered Gazi Highschool building designed by Ernts Egli and completed in 1936. Since then, the square has been subject to several interventions and changes in terms of the social values attained on it. For example, Atay, in his aforementioned novel, displays the picture of degeneration and shallowness of the square as a “disgusting” representative of the country (Gülsoy, 2009). Therefore before looking at the current conceptions of the community about the square, it is important to understand the progress that it has been up to.

5. Former discussions about the site with its surrounding definers:

5.1 Gençlik (Youth) Park:

As mentioned above the park was a part of the Ankara City Plan by Jansen, and its construction has started in 1938. At the beginning, a noteworthy portion of the public was not ready for the civilization level of the Republic (Yılmaz, 2006), that was represented with the clean and neat condition of the park. This might have been the beginning of the conflict between different portions of the society, which was going to reach at its peaks in the following times. As Yılmaz (2006) puts it, after major changes in the economy politics of Turkey in 1950’s, migration from rural to urban areas accelerated. The increase of the rates of migration to Ankara from the rural settlements occurred simultaneously with the rest of the World, which brought a different value system with itself (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012). In this period, the park has become a center of amusement and recreation, which in the second half of 1980’s hosted the peak point of conflict arisen from the encounter of the old users of Gençlik Park and those who have migrated to Ankara before having experienced a mid-class modernization process (Yılmaz, 2006). Not being able deal with the challenge brought by conflicting value systems of the divergent society, resulted with the abandonment on the spaces where that conflict occurs. Bandarin and van Oers’s (2012) express the function of city for its society: “In the experience of the majority of modern humans, cities represent the context of daily life and activity.” After 1990’s until 2008 the park was left as a neglected space, which also neglected what it stood for: the importance of daily social life (Fig.2).

Figure 2: Google Earth images of the park and Hergelen square in 2002 (above) and (2017) below.

5.2 Bank of Municipalities:

The Bank of Municipalities founded to provide financial support and management to municipalities (Güler, 1996) had a significant role on the establishment of the new modern cities of the country. The Design principles of the building require attention for the intention to be an integral part of the new environment that was going to be a long lasting representative of the strength and values of the new republic. It was a competition project won by a modernist proposal by the architect Seyfi Arkan in 1935 from out of 18 proposals (Acar, et al., 2017), one of which belonged to Martin Elsaesser (Aslanoğlu, 1986). According to Aslanoğlu, with the Mendelsohn inspired dynamism of continuous lines through semi-cylindrical forms of entrances or corners, Arkan designed his buildings with complete detailing of interiors, gardens, and furniture. Given in Acar et al.’s (2017) article on the demolition of the Bank of Municipalities Building, Arkan’s expressions on the reasoning behind the design decisions for a plain and simple building was that the focus of the environment should have been kept on the opera building which was to be built soon. As mentioned earlier, this site spared to a future opera project would become the Hergelen Square later.

Since the first rumors about the danger for its demolition for the ongoing construction on the Hergelen Square, until the day that it was demolished, it’s historic, cultural, social, heritage, and memory values were being presented and discussed by the specialists and experts, in the social media and other media that these specialists and experts could reach (eg. Cengizkan, 2015). However, these reactions did not take much place in the public press until the day that the building was demolished.

5.3 Hergelen Square and Hajek’s sculpture:

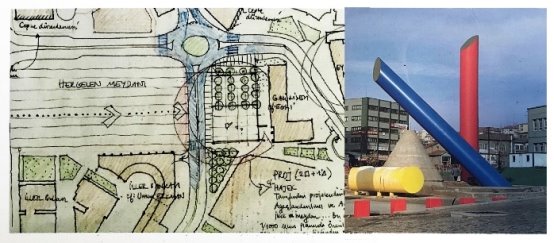

In 1986 a project competition for Ulus Historical Centre was organized and the competition winners Raci Bademli and his team’s proposal for the site included a public square and a statue to be built in front of Egli’s Gazi high school. The site that was saved for an opera building in Jansen’s plan was used by several low rise buildings, until the Ulus rehabilitation plan by Bademli was accepted. Concordant with the HUL approach that foresees an integrated cultural landscape, in his article on the design of the square, he expresses the necessity of community participation in the preparation phases of urban development projects (Bademli, 1993). In the same article he expresses the story of the decision and creation phases of the sculpture by Herbert von Hajek, in front of the Gazi High School facing the square that extends toward the train station axis through Gençlik Park, to function as a connector of the ancient past of Ankara represented by the historic citadel with that day’s Ankara (Fig.3). Regarding the design of Hergelen Square, the intention behind the renovation plan was a complete axis along the train station, Gençlik Park, Hergelen Square, Hajek’s Sculpture, architect Ernst Egli’s High School Building, and the citadel (Bademli, 1993).

Figure 3: The plan sketch of the Rehabilitation Plan by Raci Bademli and his team and Hajek’s sculpture after completion (Bademli, 1993).

The square was used as car park for decades while the sculpture neighbored an informal market where the second hand goods were sold. This is why Hajek’s sculpture could not be a part of an urban integrity. The car park and the market interrupted what that has been planned in the renovation plan by Bademli and his team, and the case with the abandoned years of the Gençlik Park is not any different.

6. The intervention in the Square

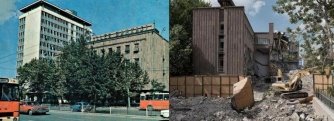

Today there stands a Mosque on the square, which looks like the mosques of the 15th century Ottoman Empire, for which Hajek’s sculpture and the registered building of the Bank of Municipalities, two cultural entities that intended to build cultural integration, were demolished (Fig.4, Fig.5, Fig.6). The construction of the mosque started in 2013 and completed in 2017. The buildings around the site were demolished so that the visibility of the mosque would not be interrupted.

Figure 4: The Bank of Municipalities building in 1970’s (Sözen, 1984) and in June 17th of 2017 (Interpress)

Figure 5: Google Earth images of the Hergelen square including the places of the Bank of Municipalities and Hajek’s sculpture in 2007 (above) and in (2017) below.

Figure 6: Views of the Hergelen Square from Gençlik Park in 2013 (on the left, the marks indicate the demolished TIKA and Bank of Municipalities Buildings) and in 2017 (on the right, the new mosque has been built).

The changes in the view from Gençlik Park, which is a part of the axis that expands to the citadel, displays the scale of the intervention in Hergelen Square (Fig.7). The following part focuses on the aforementioned questions regarding the Square and its interrupted integrity.

7. Methodology and Discussion

There are three questions that constituted the focus of this research, which are:

● Do the residents of Ankara valued a former intervention in Hergelen Square as a part of their cultural perception for the city?

● What consequences do the former disintegrated solutions have for today’s citizens?

● Does a comparison of the outcomes of the independent surveys on the public perception of the historicity of two different parts of the HUL of Ankara display a common indication about the effects of interventions in the public awareness for cultural heritage?

The study group was people who have been residing in Ankara in the past or in present. An online questionnaire was prepared and distributed through the social media tools. A total of 138 participants completed the questionnaire, and among the questions a Cronbach's Alpha level of 0,794 could be achieved through the test of the questionnaire’s reliability statistics. Although the homogeneity levels are in acceptable rates, because the asymptotic significance (2-tailed) distribution values of the rates of importance attained on the surrounding definers of Hergelen Square and the educational levels of the participants in the One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were lower than 0,05, non-parametric methods were used to analyze the data gathered from the questionnaire.

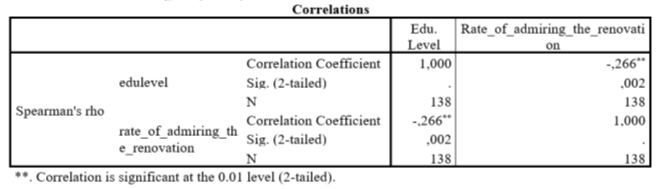

One important output that was necessary for the study is the relation between the rate of admiration of the interventions and the educational level of the participants. In the previous study on Hacıbayram Square, regarding the effect on the historic site and disintegration, a similar intervention was the subject of discussion and the outputs of the same question was significantly meaningful while there was a strong negative correlation between the rate of admiration and educational level of the participants. Below is the table displaying the results of the nonparametric (spearman) correlation test (Table 1).

Table 1. Spearman’s Correlation between the educational level and the rate of admiring the final interventions among the participants.

The correlation coefficient value on this table, which is -0,266, indicates that there is a negative correlation between the rate of admiration and educational level of the participants, which is a similar result with the survey carried out for the Hacıbayram Square. This negative correlation is significant at the 0,01 level. This test does not indicate a cause effect relationship between the two variables, however, it is possible to interpret this result that the less educated people are less questioning than the educated; or the less educated do not feel represented by the experts who constantly object to the actions taken by the government on reshaping the built environment, as the experts too are well educated people. In order to achieve a healthier outcome, the effects of other variables on the rate of admiring the last intervention should be considered. When the same test was run with the control variable of ‘age interval’, the correlation coefficient increased to -0,236, which indicated that age of the participants has an effect in the way they think about the intervention. Similarly, with a correlation coefficient value of -0,285, the control variable ‘visiting frequency of Hergelen Square’ proved to be effective for the rate of admiration of the final intervention.

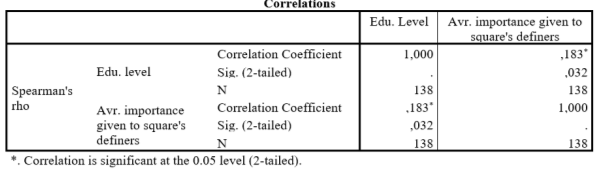

In Hacıbayram square the most significant output was the admiration of the public for the intervention on the site. The reason is that the site has a cult character that is mostly defined by its heritage value rather than the definition or design motive behind the intervention. In the case of Hergelen square however, the heritage monuments are representing an urban integrity that has been planned to be based on a shared value system from scratch. Therefore people’s appreciation of these monuments as parts of a cultural integrity also requires a major attention. Therefore, another required output is for the relation between the educational level and the average importance given to the former definers of the square, three of which were included in this study, namely Gençlik Park, Bank of Municipalities’ building, and Hajek’s sculpture. The table below displays the results of this spearman correlation.

Table 2. Spearman’s Correlation between the educational level and the average importance given to the definers of Hergelen Square among the participants.

The correlation coefficient value on this table, which is 0,183 indicates that there is a positive correlation between the educational level of the participants and the average importance they give to the square’s definers. The positive correlation is significant at the 0,05 level. Similar to the test above, this test does not indicate a cause effect relationship between the two variables, however, this result could be interpreted in a similar way with the previous outcome that the less educated people care less about the integrity of the cultural landscape than the educated.

Another question that needs to be answered was whether there is a difference in-between the values attained for the Bank of Municipalities Building and Hajek’s sculpture. The answer to this question could be interpreted to answer the first aforementioned research question. The former intervention is the rehabilitation plan of Bademli and his team, and its unachieved goal for an integrated cultural landscape.

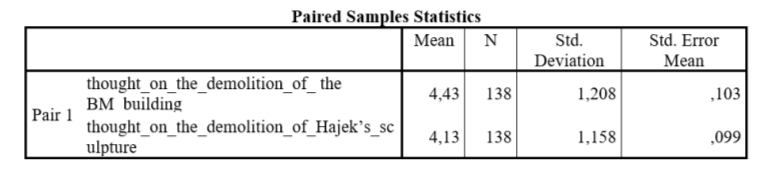

Table 3. Paired Samples Statistics among the participants thought on the demolitions of the Bank of Municipalities Building and Hajek’s sculpture

The Paired Samples Statistics table indicates that with the N value that is equal for both questions, all the participants have evaluated the demolitions of both The Bank of Municipalities’ building and Hajek’s sculpture.

Table 4. Paired Samples Correlation among the participants thought on the demolitions of the Bank of Municipalities Building and Hajek’s sculpture.

|

Paired Samples Correlations |

||||

|

|

N |

Correlation |

Sig. |

|

|

Pair 1 |

thought_on_the_demolition_of_the BM_building thought_on_the_demolition_of_Hajek’s_sculpture |

138 |

,538 |

,000 |

In the significance column of the Paired Samples Correlations, the value is 0,000, which is smaller than 0,01. This means that the participants’ thoughts on the demolition of the Bank of Municipalities’ building is significantly different than that of the demolition of the sculpture at the p < 0,01 level.

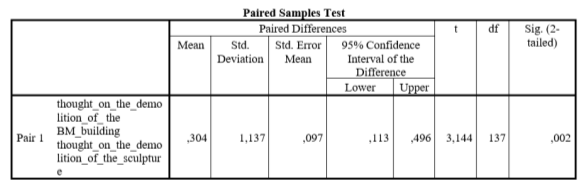

Table 5. Paired Samples test among the participants thought on the demolitions of the Bank of Municipalities Building and Hajek’s sculpture.

When the t-test results and the mean values are evaluated together, it is understood that the demolition of the Bank of Municipalities Building was found more negative than the demolition of Hajek’s sculpture. This outcome indicates that the value attained for the Bank of Municipalities is greater than the value attained for the sculpture. When considered from the perspective of the HUL approach, the Bank of Municipalities Building had a greater rate of integration with the cultural landscape. Indeed the descriptive outcome of the question regarding the demolition of the building indicates that the mean value of the 1(positive)-5(negative) scale is 4,43, which means that there is a significant disapproval of the demolition, and that the building was highly valued by the public. The mean value of the outcomes for the sculpture is 4,14, which also indicates a disapproval for the demolition of the sculpture as well.

8. Conclusions

Regarding the connection between the two sites of the same HUL of Ankara, the survey on the final intervention on Hacıbayram Square did not present an outcome regarding the changing value system of the communities, nor did its discussion could fit with the HUL approach to understand the parts of the urban fabric primarily for their integrative role. The reason for this is that both the heritage value and the religious meaning of the site constitute its dominating characteristics. However, considering these two interventions together is meaningful for understanding the common between the two interventions, and their rates of acceptance by the public. In both, the admiration rate increased while the educational level decreased, and the interventions of both were applied by the same authorities. Therefore, it is possible to say that there is consistency among the two studies regarding the relation between the educational level and the rate of admiring the interventions by the same authority.

The literature is reticent about the reasons behind the conversion of Hergelen Square into a parking space after the rehabilitation plan by Bademli and his team was applied, but it is not difficult to assume the political, economic, and primarily migration based social reasons behind this. One thing is for sure that the discontinuity between the area’s past and present is a consequence of a will that benefits from that disconnection. That the sculpture or the square did not last until today, which is unfortunately ironic considering the last words of the article of Bademli (1993), is not necessarily because of the failure of the plan or its application on the site. The disconnection in Ankara’s social and physical past and present is a normalized thing for its society.

This is not just an intervention in the physical environment. The normalization of such interventions by the local community is the consequence of an existing and previously founded problem of disconnected/interrupted/over-intervened past. The transformations happening due to other subjects’ interventions have become expectable. Disapproval of the demolitions is clear, but the resistance remains passive. Regarding the results of the study, it is possible to say that for the last intervention, the rate of appreciation is very low, but the reaction against the intervention is limited with a very small portion of the public.

Being registered has not been enough to protect the Bank of Municipalities Building, and in the 17th of June in 2017 the registration was removed and the demolition begun irreversibly in the same day. The explanation of the reasoning behind the removal of its registration was the loss of its structural durability and being severely exposed to corrosion. It is not possible to discuss here whether the technical reports, which were given as the reason behind the removal of the registration, reflected the truth about the buildings durability. However, it is possible to be highly skeptical about it, especially regarding the last three years of the life of the building. The story is well known by those who are interested and the presupposed reasoning behind the demolition is shared among those who feel sorry for its ending.

From the point of the HUL approach the demolition of the building of the Bank of Municipalities is not only a loss of a historic monument as a single building with historic significance. More predominantly, it is the loss of the urban integration that it provided to determine the comprehensive system of an urban historic area as it is expressed in the Vienna Memorandum of 2005 (Bandarin and van Oers, 2012). Unlike Hajek’s sculpture, that had been blocked by the parking area and market for decades, the Bank of Municipalities building had not lost its role in maintaining that integration, which is apparently concordant with the reasoning behind Arkan’s design decisions like modesty, continuity, relation with the boulevard on the ground floor scale. It was an ultimate example of consistency and success not only as a product of architecture but also for its 80 years’ role of place-making. Together with Hajek’s sculpture it was sacrificed to build a pseudo context that is completely disintegrated with the place’s cultural value system. Apart from that, the most important output that can be derived at the end of this study is that if the HUL approach was adopted, and if the public took a responsibly participant role in the decision making processes on informing those who are in charge about the acceptable limits of change, the condition could have been much different than today. There is no clue whether the integrating proposal of Bademli and his team would accompany the resilience of the community, as well as the sustainability of the cultural landscape. However, it is for sure for today that the possibility of applying a similar approach with that of Bademli for achieving the integration of the cultural landscape of Hergelen Square is far less than it was in the past.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. Adile Nuray Bayraktar for her helpful support in reaching the required information, and to all of the participants of the questionnaire. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Acar, M., Koçer, Ç., & İmamoğlu, B. (2017). Urban regeneration or degeneration? Demolishment of İller Bankası building as a representation of cultural heritage. Urbanistica Informazioni, 272, 334-338. http://www.urbanisticainformazioni.it/IMG/pdf/ui_272si_04_sessione_04.pdf

Alpan, A. & Açıkgöz, E. K. (2017) “Multi-cultural Perception of the Cult Site of Hacı Bayram in Historic Center of Ankara” in the proceedings of the International Congress on “Preserving Transcultural Heritage: Your way or my way?” (05-08 July 2017, Lisbon, Portugal). DOI: https://doi.org/10.30618/978-989-658-467-2_49

Aslanoğlu, İnci. (1986). “Evaluation of Architectural Developments in Turkey within the SocioEconomic and Cultural Framework of the 1923-38 Period”, METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, 7(2), 15-41. http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/1986/cilt07/sayi_2/15-41.pdf

Atay, O., (1984), Tutunamayanlar [The Disconnected ], İstanbul: İletişim.

Bademli, R. (1993). Hergelen Meydanı [Hergelen Square], Ankara Söyleşileri. Ankara: TMMOB Mimarlar Odası Yayınları, 7-11.

Bandarin, F., & Van Oers, R. (2012). The historic urban landscape: managing heritage in an urban century. John Wiley & Sons. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2014.909618

Cengizkan, N. M. (2015), “Moderne Yönelik Yeni Bir Yıkım Tehdidi Daha: Seyfi Arkan’ın İller Bankası Binası [Another threat of demolition for the Modern: Seyfi Arkan’s Building for the Bank of Municipalities]” Mimarlık, 381. http://www.mimarlikdergisi.com/index.cfm?sayfa=mimarlik&DergiSayi=395&RecID=3565

Gülsoy, M. (2009). 602. Gece: Kendini Fark Eden Hikâye [The Night: The story that recognizes itself]. İstanbul: Can. ISBN 975072271X, 9789750722714 https://www.dr.com.tr/Kitap/602-Gece/Edebiyat/Edebiyat-Inceleme/urunno=0000000309721

Harvey, D. C. (2001) Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7(4), 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13581650120105534

Mydland, L., & Grahn, W. (2012). Identifying heritage values in local communities. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18(6), 564-587. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.619554

Ripp, M., & Rodwell, D. (2016). The governance of urban heritage. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 7(1), 81-108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2016.1142699

Sözen, M. (1984). Cumhuriyet dönemi Türk mimarlığı [Turkish Architecture of the Republican Period], 1923-1983 (No. 246). Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları.

Taylor, K. (2016). The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landscape Research, 41(4), 471-480. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1156066

Turner, M., & Tomer, T. (2013). Community participation and the tangible and intangible values of urban heritage. Heritage & Society, 6(2), 185-198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X13Z.00000000013

Van Oers, R. (2010). Managing cities and the historic urban landscape initiative–an introduction. Managing Historic Cities, 7-17. ISBN: 9230041750, 9789230041755 http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?catno=189607&gp=1&mode=e&lin=1

Yılmaz, B. (2006). “Bozkırdaki Cennet: Gençlik Parkı [Paradise in the Steppe: The Youth Park]”, Sanki Viran Ankara, İstanbul: İletişim, 211-236. ISBN: 9789750504464

https://www.iletisim.com.tr/kitap/sanki-viran-ankara/8017#.XAEzO-gzaUk

Zeayter, H., & Mansour, A. M. H. (2017). Heritage conservation ideologies analysis–Historic urban Landscape approach for a Mediterranean historic city case study. HBRC Journal, Elsevier. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2017.06.001