1. Introduction

Reviews of many renowned projects reveal that the level of successful community participation in architecture and urban design projects affects the sustainability of the added value of such projects in their contexts. This paper aims to question the level of success of a contemporary architectural milestone in Egypt; namely the Aga-Khan Award winning project of the Child Park in Sayyeda Zeinab - designed by the Egyptian architect Abdel-Halim Ibrahim; from a community participation perspective. The Children Park was complemented by the project of Abu-ElDahab Pedestrian Street, both projects functioned collaboratively to respond to the needs of the adjacent community and establish the participatory approach for a sustainable development. After 28 years of its initiation the study revisits the project which was launched with much publicity raising high hopes to achieve its noble aspirations. The methodology adopted in this paper as shown below in (figure 1), is based on primarily, a literature review of the community participatory approaches in contexts of Heritage Value, followed by intial ceremonial particpatory process of building the Park and the intial role intended by the architect whether related to the park itself or to the adjacent Abu-ElDahab Street. Following that a qualitative analysis of the current state of the park and adjacent street is conducted, based on site investigations, behavioral mapping of the current status, analysis of the roles of the beneficiaries, interviews conducted with different stakeholders about the present challenges of the role of the park in the district. Based on those two main research approaches, the paper concludes with a framework and several guidelines to enhance the social sustenance of the context through rephrasing the park’s role in relation to the changing needs of the community.

Figure 1: Research Methodology

2. Theoretical Overview to Community Participatory Approaches in Contexts of Heritage Value.

According to (Bens, 1994), the international scale resources for social welfare services are becoming very limited. This is due to the pressures of population increase and the consequent changing priorities of governments. and the changing priorities for governments, (Bens, 1994). Thus, the utilization of non-professionals through citizen involvement mechanisms to address social problems has become more applicable in addressing the development demands of local communities, (Kaufman and Poulin, 1996).

The term community participation is itself a rich concept that differs according to its application and definition. The way participation is defined also depends on the context in which it is implemented. The definitions selected here focus on the main spectrum of interest of this specific research study. Oakley and Marsden (1991) defined community participation as the process by which individuals, families, or communities assume responsibility for their own welfare and develop a capacity to contribute to their own and the community’s development. In the context of urban development, community participation refers to a dynamic process in which the beneficiaries influence the direction and execution of development projects rather than merely receive a share of project benefits (Bamberger, 1991). As to Arnstein (1969), citizen participation is the same as citizen power. However, she argues that there is a critical difference between going through the empty ritual of participation as a process only and having the real power needed to affect the outcome of the process itself.

In the realm of urban development, participation in housing and urban service management is a process where people as consumers and producers of housing and urban services are involved in the planning, implementation and maintenance of the projects. Participation is based on voluntary relationships between various actors, which may include government institutions, individual housing and urban services users, community-based organizations, user groups, private enterprises, and non-governmental organizations, (Nour, 2011).

Nour (2011) further asserts that the concept of participation in development is certainly not a new one. According to Moser (1987), in rural development, community participation has been evidenced as an important success factor since 1950. This is evidenced through experiences with participatory housing and urban development projects which show that

community-based organizations and housing users can make important contributions to the provision and operation and maintenance of housing and urban systems. Benefits are achieved not only from reducing cost and active resource mobilization, but also from better targeting of project measures to peoples' real needs through their involvement in the planning phase, which will be further evidenced in the case study.

In addition to that as Nour (2011) proposes, participation enhances the "ownership" of the facilities by the involved community and thus ensures maintenance and sustainable use of facilities and more reliable operation. From another dimension, Rashed el al., (2000), focus on the importance of paying special attention to community participation while dealing with the issue of heritage conservation. This was evidenced in the restoration projects handled by Rashed in the conservation projects implemented in Quseir city. Local community participation within participatory environment, from the very beginning, was the policy adopted. Involvement and sharing with the people of Quseir started with the planning and strategy of work as well as using workers and technicians from the city people in the execution phase, (Rashed el al., 2000). This helped the engagement of the community in the process in a way similar to what will be explained in the case study below.

3. The Role of Community Participation in Achieving Social Sustainability

As addressed in the definitions and understanding of the term community participation, the issue of participation in development is intertwined with the sustainability of the implemented planning or project. The level in which the community gets involved varies. In order to understand the possibility of community participatory approach, the Arnstein ladder will be used as a reference model.

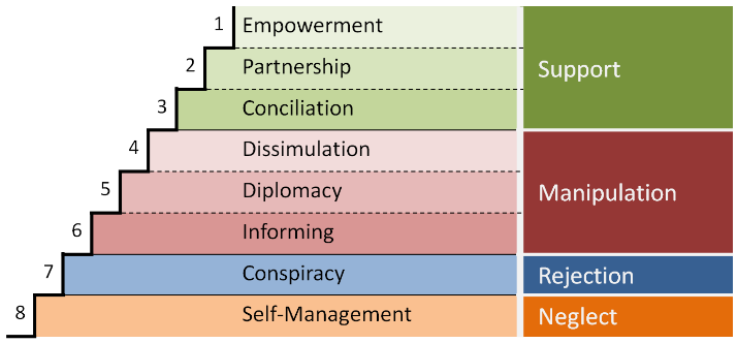

According to Choguill (1996), the best known attempt to determine the scale of participation by the public is that of Arnstein. She views citizen participation as a term for citizen power. Thus, Arnstein defines participation as "the redistribution of power that enables the have-not

citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately

included in the future”. Arnstein categorizes the levels of involvement in the form of a ladder

composed of the following milestones, empowerment, partnership, conciliation, dissimulation, diplomacy, informing, conspiracy and self-management, (figure 2).

Figure 2: Arnstein’s Ladder of Community Participation, Choguill, 1996.

As Choguill (1996) explains, supportive governments help achieve the first three levels of participation, namely empowerment, partnership or conciliation, depending on the degree of governmental willingness and/or confidence in the community's ability to contribute to the development process. Not-so-supportive governments will hide their discouraging attitude in an unskillful and sometimes very destructive approach to the problem, because it demobilizes an otherwise more effective organization of the people for the self-help they need. In this case, there is no clear/effective opposition to the community organization/activity, represented by several kinds of manipulation. When the poor are not yet ignored by the government, but rather they are seen as an inopportune and unwelcome group to be eradicated at any cost, a clear governmental opposition may result in a fearsome conspiracy. This is usually manifested as destructive governmental top-down projects which stimulate community solidarity and violent reaction, Choguill (1996). This model will help in understanding the level of changing community involvement in the case study, in relation to governmental support and the sustainability of community participation in the operation of the park.

In addition to that as Enyedi (2004) explains, it is crucial to create a dialogue between decision makers and user groups as a pre-requisite for sustainable urban development. Towns and communities constitute the basic unit of local government in a democratic state. This is the level at which citizens come into direct contact with the state and the authorities in conducting their everyday affairs. Sustainable urban development depends to a very large extent on whether the public’s encounter with democracy at the local level is a stimulating and satisfactory experience. It is evidenced that urban conflicts generate social exclusion which leads to deteriorated urban environment and political instability, Enyedi (2004).

In order to achieve sustainable public participation, the process can be implemented as a formal or informal procedure. This procedure can be led either by formal decision maker’s intervention, or through informal designer led procedure as will be explained in the process of design of the Child Park.

4. Design Approaches and Philosophy of Aga-Khan Award winning “Community Park”

This part will briefly explain the design process of the local case study which is the Child Park, depending of academic articles by the architect and other scholars. This explanation will be linked to the previous literature review to discuss the levels of community participation in the process as well as the sustainability of the participatory approach after years of operation and discuss the dilemma between intended values and implemented operations. It is important to note that the project was awarded the Aga Khan Award based on the community participation in the design process rather than an end product.

The official name of the project is the ‘Cultural Park for Children’; the park designer, Architect Abdel Halim Ibrahim mostly refers to the project as ‘the community park while the manager simply describes it as ‘the child’s park’. In between ‘community’ and ‘child’ lies the conflict between the architect and the manager about the role of the park and its functional appropriateness. The ‘community park’ reflects the architect’s interest in the development of this community through the projection of his theoretical background, which is braced by the architect’s belief in the park as ‘an educational instrument’ (Saleh, 1989). The manager on the other hand showed more interest in the child’s everyday activities in the park. In other words, the architect read people through the wider social context of place, community, while, the manager read people as child’s activities within place, Abdel Wahab (2009).

The architect introduces the event through a ‘Building Ceremonial’, which involved building up a full scale model in wooden poles and canvas of the fountain and exhibits, whereas oneplatforms and terraces were marked on the ground. Dancers, musicians and artists were invited to participate as well as the community of Al-Houd Al-Marsoud. The intent was to show the community how the project would be; this is not part of the contemporary Egyptian building culture, Abdel Wahab (2009).

According to the architect and designer of the park, the life and environment of the communities are regulated by an imposed, top-down process of planning and production which draws its principles from sources dislocated to the community and its cultures. The result is underdevelopment, and waste and destruction of the environment and its resources. The architect regards any environmental plan in context of these developing communities

should be taken as an opportunity to re-establish the relation between the culture and the production of its environment. The responsibility of the architect in any public project in this context is to re-establish that relation; hence, the fundamental task of architecture is to try to understand local life, and search for the mechanisms that bridge the gap between technology and society, the material and spiritual, and become once more vital to communities in the process of the rejuvenation of their identities, (Ibrahim, 1996).

The design concept was based on layers of symbols and of bridging the missing gap between the community and the park, (fig.3, 4). The first layer is the formal layout inspired by the spiral pattern whereby the components of the project are organized around the palm-tree promenade. The existing trees of the earlier Al-Hod Al- Marsoud garden were maintained and reinforced, becoming the main axis for the conceived geometry of the park. The starting point of this geometric order is, fittingly enough, also the place for water, the source of life and growth. The end point is a lone tree at the other extremity of the palm-tree axis. The site is then organized in stepped platforms following the geometry created by the spiral. The platforms move upwards toward the middle of the site to form an arena-like park, and then they turn in the opposite direction forming a downhill arrangement towards the end of the site where the museum is located. The theatre is situated at the turning point of the two movements. Those three elements, the water point, children’s museum, and the theatre are the main poles around which sets of activities, and hence meanings, are created within the realm of the park, (Ibrahim, 1996).

Figure 3: Development of Park Design Concept, Ibrahim, 1996.

Figure 4: Park Design Entry in the Competition, Ibrahim, 1996.

The second layer is a circumstantial layout resulting from the ceremonial process. The building process was organized in a series of events, each of which combined technical work with cultural aspects of that particular operation. The park was built in stages, and the precise shape of each stage was defined as the work progressed. The building ceremony was thus not simply an empty ritual but a dynamic process where the static order of the original blueprint became flexible. Actual communication was established with local residents and creative decisions regarding how best to integrate the project into the community ensued, giving legitimacy to the process. Ideas and images emerged for the park that would not have transpired in the sterile environment of an architect’s drawing office (Ibrahim, 1996).

In addition to the previous layers, the park wall, rather than preventing access, as is common in Cairo, became permeated by a series of openings to allow access to cultural facilities beyond. Again, in order to create a practical link between the service strip and abutting neighbors, the side street was pedestrianised. In addition, the Cairo Governorate was successfully lobbied to overrule an old expropriation law that prevented the renovation of the houses overlooking this street. Once residents were assured that their homes were not going to be demolished, they set about repairing their apartments, thereby upgrading the entire area.

In our case, the surrounding community became vibrant with activities. Residents upgraded their homes, street weddings and festivals became once again a feature of the community. For two years they celebrated the impact of the park in improving their environment, (Ibrahim, 1996).

However, after those two years, the official neglect by local authorities and the lack of institutional mechanisms at the community level to make up for this neglect led to the gradual deterioration of the street again. With no regular maintenance, elements like street lighting and regular garbage collection disappeared. As a result, the area once again appeared deserted and invited acts of vandalism from outside the area against the park. Drugs and prostitution, after being driven away for two years, reclaimed the territory. The proposed studios, shops, and community cafe along the side street, which were initially met with the much enthusiasm, failed to materialize due to government bureaucracy and now their establishment is looked on with skepticism and doubt. In response to formal mismanagement and the general sense of apathy in the community, some members chartered a community-based organization called the Abu Dahab Street Association to address these problems. Since its establishment the association has helped improve security in the area by lighting the streets once again and ensuring that they remain so. All these are positive indications of a community trying to have a bigger say in the nature of their surrounding urban environment and make the impact of the park in upgrading the area sustainable, (Ibrahim, 1996).

Based on observations later by Abdelwahab (2009) a significant change in the park is evident later after the published articles by the architect. The realities of the park’s everyday life, and Abu Al-Dahab Street in particular, shows indifference to the original design scheme, creating conflicting community activity and isolating the park from Al-Sayyida Zeinab context. This change is also manifested through a conflict between the architect and the manager of the park (Hassan, 1996), where the manager intervened in the design and made several changes to the park. Thus, the next analytical part will present the current case of the street and the parkk in order to re-visit the valaubale addition in the Cairene context. The analysis will be based on behavioral mapping of the activities in the park and the adjacent street during different times of the day, walk throughs and observations and finally interviews with the main beneficaries of the zone.

5. Analysis of the Current State of the Park and the Adjacent Abu-Eldahab Street”

The next part will cover the analytical part of the paper, based on site visits during various timings for the park and the adjacent Abu-Eldahab Street. The fieldwork coincided with the annual ceremonial event of Al-Sayyeda Zeinab’ “Mulid“, a religious ceremony where a considerate number of the Sufis visit the place to pay tribute to the Prophet’s daughter on the assumed day of her birth.

During the period of the study, the space was occupied with the Moulid activities event, in addditon to the original everyday ones. It has to be acknoweldged here, that the illustrations of the behavioral mapping were conducted by students enrolled in a Double Matsers Degree program by BTU Cottbus and Cairo University; and supervised by the authors of the paper. The students' contribution to the research is greatly useful in this context.

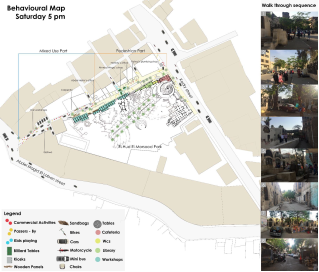

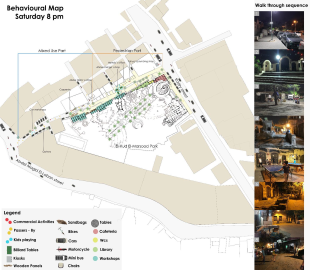

5.1 Behavioral Mapping of The Park And Its Context

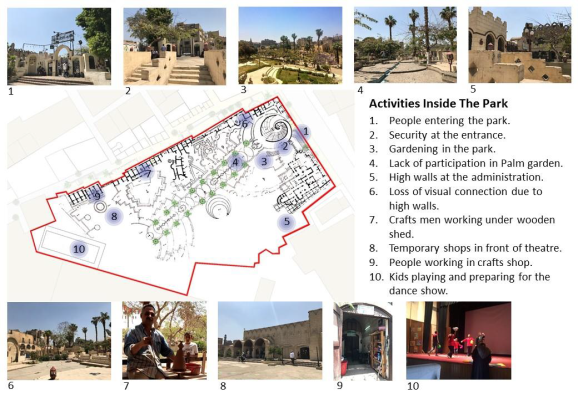

The Park is currently forming a strict boundary between the residents of Sayyeda neighborhood. As apparent in (figure 5), the park is surrounded by impermeable walls from all sides, with the main and sole access is from the main street. Visitors of the park have to cross a security gate which embodies a strong territorial definition. Then, the security only allows children, or schools’ teachers accompanying school trips or organizations for disabled children. Parents are not allowed to accompany their children, which creates a gap between the users and the place, especially with the lack of visual connectivity between the outside and the inside. As shown in the map, the main attractions for children were associated with the traditional mud crafts, and the talents show organized by an organization for mentally retarded children in the theatre at the end of the axis inside the park.

In the meanwhile the fountain zone, the open amphitheatre and the library rooms remain unoccupied; since the school trip is scheduled to use the closed theatre solely and children cannot move freely in the park. The activities in the park do not follow a voluntary pattern of use, the supervisors plan a designated schedule which leaves most of the park area unoccupied for most of the day.

Figure 5: Overview of Activities Inside the Park, BTU-Cottbus Double Msc Degree Students, 2017.

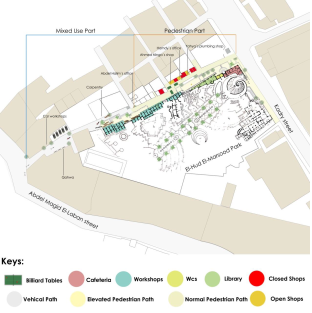

As to the pedestrain street, Abu El-Dahab Street, it shares its entrance from Qadry street. The street has a wide entrance with palm trees and evergreen trees yet it has cars parking in this entrance which make it look narrower, the street is spitted into two halves the first half is adjacent to the park and it has the shops doors which are totally vacant and closed. This part is elevated with some steps. While the other side is on the zero level and is adjacent to the residence and local shops. This difference in the street levels, although intended by the architect to create a special realm for the retail shops and to allow more street activities, resulted in the case that it segregates the park even more from the adjacent neighborhood due to the current lack of activities adjacent to the park’s wall whatsoever.

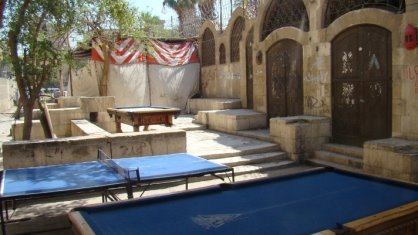

Unfortunately the behavioral mapping and the observations show that the street is dead most of the time which is exaggerated by the absence of vehicular traffic as well. There are few active zones, as shown in figures 6, 7 and 8, which cover the behavioral mapping for the same place during different times of the day. The first one was the zone of “Ahmed Ninja” shop, which provides recreational activities for the youth in the neighborhood. The shop extends three billiard tables in the street, attracting youth playing billiards and others waiting for their turn, otherwise the place is so calm and most of the shops are closed. The second active zone is the wood workshops and little leftover wood in front of it. In this zone the street changes from pedestrian to Vehicle Street. The third active zone is at the end of the street, where car repairing shops with a coffee shop for people to wait for their cars there.

Figure 6: Activity and Users’ Mapping of the Park and adjacent street, BTU-Cottbus Double Msc Degree Students, 2017.

Figure 7: Behavioral Mapping of the Park and Street, BTU-Cottbus Double Msc Degree Students, 2017.

Figure 8: Behavioral Mapping of the Park and Street, BTU-Cottbus Double Msc Degree Students, 2017.

5.2 Walk through and site observations

In addition to the behavioral mapping which showed the various activities inside the park and in the adjacent street during different hours of the day, the authors conducted three consecutive walk through visits to highlight the major community oriented activities which take place in the park’s territory. The first visit was on the weekly holiday of Egyptians, which is Friday, (figures 9 and 10). As obvious in the photos, no activities related to the community were taking place on this vibrant day. As a matter of fact, only exceptional entry to the park was granted to the researchers based on a letter for research facilitation. However, no children were allowed in on the holiday, because since the operation was held though the ministry of culture, the employees were also given that day a holiday. From another side, the pedestrian street appeared vacant and deserted as well, since no community oriented activities are taking place anymore.

Figure 9: View inside the Park on the weekend holiday, Authors, 2018.

Figure 10: View from Abu-ElDahab Street Entrance, Authors, 2018.

The second site visit was organized during a working week day. As shown in figures (11 and 12), the two main magnets for community activities were the theatre and the traditional arts corner. The theatre was exhibiting a homemade crafts exhibition and market whose income will be subjected to disabled children. This was organized by a national governmental school. However, due to the previously explained operational procedures, the visitors were merely the schools’ teachers and children from the National school. Those observations and site visits reflect the de-attachment between the park and community in a dramatic way. The park turned into a governmental type of building, rather than a positive community collector for various standards and age groups to engage and celebrate as initially intended in the building ceremony by the architect.

Figures 11. Activities Inside the Park, Authors, 2018.

Figure 12. Activities Inside the Park, Authors, 2018.

The final field visit was conducted during the annual celebrations of Sayyeda Zeinab’s “Mulid”. As shown in figures 13 to 17, the pedestrian street seemed the most active in that period of time. Visitors from all over the country come to attend the celebration, one week beforehand. They build temporary prayer and accommodation spaces. However, celebrations and community interactions are limited to the outer walls of the park. No celebrations are admitted inside the park. Also, during the peak times of celebrations, the park operators close the park completely to avoid clashes with the visitors of the “Mulid”.

The outer walls of the park are used as supports to the temporary structures. The mulid woodens posts and traditional tents are constructed with the approval and permission of the local authorities who are also present in the scene to restore order and ensure the safety and security of the worshipers and residents. The celebrations are never admitted inside the park; during the peak days of Mulid, the Ministry closes down the park completely to avoid clashes and disturbances from the “Mulid” visitors. Also participation in the Mulid is limited to Suffi worshipers; who are mostly strangers and not necessarily members of the community. The orginal residents and community members prefer to stay indoors during the Mulid and leave the streets to worshipers.

Figures 13 & 14. The Park’s Walls, Authors, 2018.

Figures 15&16. Celebrationd of the Mulid in Abu Eldahab Street, Authors, 2018.

Figure 17. Mulid Temporary Structures in Abu-Eldahab Street, Authors, 2018.

|

|

|

5.3 The Role of the Beneficiaries and Stakeholders Interview Summary

The last point of analysis to be adressed in this paper, is the analysis of the roles of beneficiaries and stakeholders. The analysis focuses at this point on the roles of stakeholders and beneficiaries of the project; represented by the groups and individuals who can affect and/or be affected by decisions and actions related to the park and street. Stakeholders often reflect diverse and conflicting interests and concerns. In addition; different stakeholders have different degrees of involvement at the community level and accordingly are addressed differently in the research analysis. Even though the park was initiated as a gathering point for all members of the community equally, at the present time the beneficiaries of the project are divided into two identifiable groups; those involved with activities inside the park, and those who operate outside it in Abou ElDahab street.

Inside the park the Ministry of Culture is the owner and operator who controls the park and all the personnel associated with it, the administrators, employees, craftsmen, and security staff. The users are children with special needs. In Abu-ElDahab section the municipality with its police force and regulations controls activities on the street. The users of the street include residents of adjacent buildings; passers-by and customers interested in services provided along the street; and finally the stakeholders or the private sector represented by shop owners who influence activities in the pedestrianized section of the street; namely the owner of the youth games center, kiosk owner, plumber, and carpenter. At the vehicular end of the street the coffee shop owner and car repair mechanics control the scene.

In addition, Abou ElDahab Street one established an organization formed by different stakeholders with the objective of sustaining the participatory project by means of operating the shops built within the park wall as an arts and crafts center. The center would be leased by the ministry to local craftsmen and would establish the economic backbone to the project. The shops income would be the main resource supporting the organization. This financial and economic scenario was never implemented due to the change in policy exemplified by the change of the Minister of Culture. In absence of resources the project lost its main element of sustainability; and since then the idea of community participation was dismantled gradually

The Ministry of Culture - the main authority in the park - operates it as a governmental bureau; changing craftsmen, artists and landscape designers into administrative employees; waiting for guranteed salaries hoping to exert minimum effort and spend less working hours in the park. concern is that any intervention of the park's operational system would make them work harder or for longer hours.

Interviews with the children - the end users of the park - reveal that they are hoping for more exciting activities and extend working hours of the park. They hope for a park where all are admited equally to share the fun of the gatherings. Despite the concern of overcrowding the park; they still hope to be joined by their parents and peers in special events. Accordingly, it can be observed, that the lack of sustainable management of the park leads to diverse and conflicting aspirations between the project's benefices.

6. Discussions

Based on the conducted analysis, it is crucial to start a new participatory process that integrates all concerned entities to reach a sustainable approach in which the park and the street can play a vital role in developing the community. The gap which is now occurring is expected to widen with time. Therefore, a comprehensive approach could be initiated by one of the local community organizations to adopt a strategy to strengthen social cohesion, foster local economy and promotes physical environment.

7. Conclusions

The research studied one of the important milestones of contemporary Egyptian architectural additions. Although the Aga-Khan award winning park aimed to create community mobilization, the case nowadays is the complete opposite due to the operation and segregation of the park from its original role. It is highly recommended after the course of this research to maintain a sustainable approach based on social participation, economic sustainability and architectural upgrade to re-attract users to the park in order to maintain its original intended role in the community.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Abdelhalim, I. (1996). Culture, Environment, and Sustainability: Theoretical Notes and

Reflection on a Community Park Project in Cairo. Sustainable Landscape Design in Arid Climates. William Reilly (Ed). Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

https://archnet.org/sites/775/publications/2611

Abdel Wahab, M. (2009). Reading Place: The Cultural Park for Children. FORUM Ejournal, 9, 1-12.

https://research.ncl.ac.uk/forum/v9i1/Papers/Abdelwahab%20(2009)%20Reading%20Place.pdf

Arnstein, S. (2007). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Bamberger, M. (1991). The importance of community participation. Public Administration and Development, 11(3),281–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230110317

Bens, C. (1994). Effective citizen involvement: How to make it happen. National Civic Review , 83(1), 32-39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.4100830107

Chougill, M. (1996). A Ladder of Community Participation for Underdeveloped Countries. Habitat International, Elsevier Science Ltd, 20(3), 431-444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(96)00020-3

Enyedi, G. (2004). Public Participation In Socially Sustainable Urban Development. PCCS, Hungary: UNESCO/MOST Program and Centre for Regional Studies (Hungarian Academy of Sciences) with the co-operation of MTANITA Foundation (Budapest, Hungary) and the Hungarian MOST Liason Committee. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001355/135555eo.pdf

Kaufman, S. and Poulin, J. (1996). Coherency among Substance Abuse Models, Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 13 (3), 163-179. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com.eg/&httpsredir=1&article=2358&context=jssw

Marsden, D. and Oakley, P. (1991). Future issues and perspectives in the evaluation of social development, Community Development Journal, 26 (4), 315-328. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/26.4.315

Moser, C. (1987). Approaches to community participation in urban development programs in third world countries, In Bamberger, (Ed). (1987). Readings in Community Participation. Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-9006(89)90010-X

Nour, A. (2011). Challenges and Advantages of Community Participation as an Approach for Sustainable Urban Development in Egypt.Journal of Sustainable Development, 4(1), 79-91. http://www.cpas-egypt.com/pdf/Ayman_Afify/9th%20Paper.pdf

Rashed, A., and ElAttar, M. (2002). Dialog between sustainability and archaeology: A case study of the Ottoman Quseir fort. Retrieved April 1st, 2018, from http://www.cpas-egypt.com/pdf/Ahmed_Rashed/010-%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20Quseir%20paper.pdf

Rashed, A., and ElAttar, M. (1999). Local Community Options for Sustaining Heritage: Case Study Quseir City. Retrieved April 1st, 2018, from http://www.cpas-egypt.com/pdf/Ahmed_Rashed/011-%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20Attar%20Qusier%20paper.pdf

How to Cite this Article:

SHAFIK, Z., & EL-HUSSEINY, M.-A. (2019). Re-visiting the Park: Reviving the “Cultural Park for Children” in Sayyeda Zeinab in the shadows of Social Sustainability. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs, 3(2), 84-94. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.4704

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivs 4.0.

"CC-BY-NC-ND"